|

|

Table

of Contents

Explorations

of the West

Sam

Dalsheimer

Caitlin

Goss

Nick

Schradle

David Sena

Representations

of

Native Americans

Richard

Dybas

Amanda Leong

Cynthia

Robertson

The

Western Railroads

Ronni Toledo

Kayt

Fitzmorris

Jon Ingram

David

Halperin

The

California

Gold Rush

Jordan Helle

Adam

Lawrence

Marisa

Pulcrano

Patrick Ryan

California

as Western Destination/

Mediterranean Boosterism

Maddy

Kiefer

Danielle

Mantooth

Molly

Nelson

Stefanie Ramsay

Other Online

Exhibits

|

Introduction

The exploration texts of Lewis and

Clark, John C. Fremont, and Charles

Wilkes demonstrate a large array of

American sentiments of the early

19th century towards the frontier.

In these texts there is an

increasing audacity in tone as the

explorers grow more confident with

the lay of the land.[more]

This confidence is indicative of the

United States’ growing comfort with

the western territories and its

changing values as seen through the

doctrine of Manifest Destiny. All

four expeditions were sponsored by

the United States government with

very strict goals of cataloging the

landscape and wildlife (the natives

also being part of the “wildlife”)

and how to best manipulate them. The

language of these narratives is

scientific and analytical on all

accounts but especially towards

Native Americans. What started as a

gentle yet patronizing interest by

Lewis and Clark turned into scorn

and distrust in Fremont and finally

transformed into Wilkes’ near

blatant racism towards the natives

and espousal of white superiority.

Also distinguishing these texts is

the fact that they were all written

by military men. Their training and

propensity to evaluate situations

based on fulfilling the United

States government’s expectations not

only make for highly

professionalized documents but also

indicate a martial attitude towards

the domination of a land and its

people.

|

|

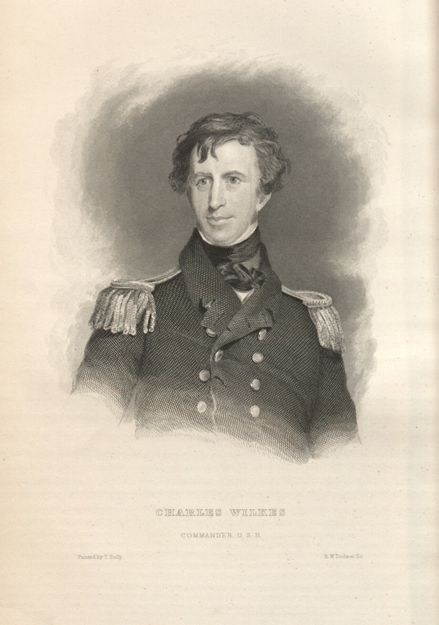

Narrative of The United

States Exploring

Expedition:

During the

years 1838, 1839, 1840,

1841, 1842

- Sam Dalsheimer

"Charles Wilkes:

The Most Intrepid Man of All

Time"

The United States Naval

officer, Charles Wilkes was

tapped by the U.S.

government in 1836 to lead a

large group of scientists,

artists and linguists, to

explore coastlines, islands,

and the general periphery of

the United States

territory. His

officially penned

documentation, the Narrative of the

United States Exploring

Expedition,

is an expansive text (much

like the frontier) covered

in five volumes each, each

reaching over five hundred

pages. Wilkes and his

men journeyed from Virginia,

circumnavigating South

America, and eventually

reached Fiji, Hawaii,

Vancouver, Oregon,

California, and numerous

South East Asian islands.

The illustrations in every

volume are exquisite.

The depictions of craters

and volcanoes in Hawaii are

particularly

mesmerizing. When in

Oregon, Wilkes expounds on

the “primeval forest of

pines in the rear of

Astoria,” noting the largest

tree to have a circumference

of thirty-nine feet six

inches; a camera lucida

drawing by one of their many

artists, J. Drayton, gives

an impressive sense of the

scale of these towering

pines.[1]

Throughout the

narrative Wilkes employs a

very methodical and

scientific approach to

writing. This of

course fits well when

cataloging the flora, fauna,

and geography, but he

carries the same tone when

describing the native

population. Even at

his most pro-Indian, Wilkes

uses dehumanizing, technical

words. He describes

their native pilots, Ramsey

and his brother George, as

“good specimens of Flathead

Indians;” furthermore, he

was “pleased at having the

opportunity” to include

sketches of them,[2] much

like the drawings of plant

life that litter the rest of

the document.

There are times when Wilkes’

racism is shockingly

blunt. At one point he

describes the “vicious

propensities” of the

indigenous population in

Astoria:

Both sexes are equally

filthy, and I am inclined to

believe will continue so;

for their habits are

inveterate, and from all the

accounts I could gather from

different sources, there is

reason to believe that they

have not improved or been

benefited by their constant

intercourse with the whites,

except in very few cases. It

is indeed probable that the

whole race will be

extinguished ere long, even

if no pestilential disease

should come among them to

sweep them off in a single

season. [3]

This is admittedly one of

the more extreme examples of

racism in the text, but it

is intriguing nonetheless,

especially when analyzed via

postcolonial theory. Wilkes

engages in Orientalist

discourse by analyzing the

natives, “not as citizens,

or even people, but as

problems to be solved or

confined or as the colonial

powers openly coveted their

territory–taken over."[4] Of

particular note is his

interpretation of

miscegenation, which plainly

acknowledges a belief that

whiteness would bring some

sort of “improvement” to the

lives of natives.

Regardless of the inherent

racism in the text, Charles

Wilkes’ writes with a

professionalism that many

original source accounts

lack. In particular,

the attention to detail is

impressive for such a

massive endeavor. If

we ignore the fact that

Wilkes considers Indian aid

as some auxiliary effort to

the expedition much of the

time, we can see that

indigenous groups were

incredibly helpful–at times

essential–in making the

travels possible; within

every few pages, trade with

Indians is mentioned.

Wilkes’ rhetorical

choices—in depicting the

indigenous

population—further

legitimize the continued

colonization of the American

landscape in the

mid-nineteenth century.

Return to Top

|

|

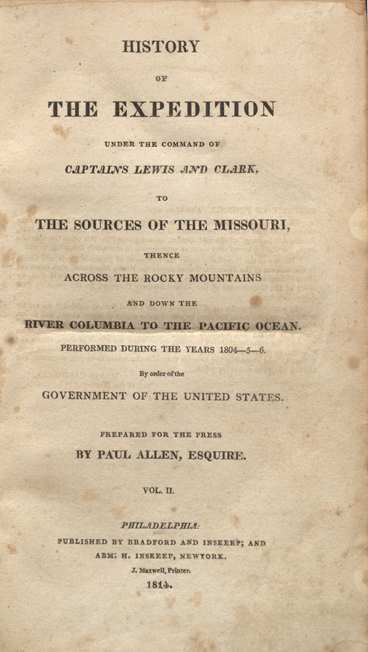

History of the expedition

under the command of

Captains Lewis and Clark,

to the sources of the

Missouri, thence across

the Rocky Mountains and

down the River Columbia to

the Pacific Ocean,

Performed during the years

1804-5-6

- Caitlin

Goss

"Lewis and Clark

Explore the West"

The exploration of the west

is a hefty topic and one

that can be theorized in

many ays from the

ideologies of Frederick

Jackson Turner’s rugged

frontierism[1] to William

Cronan’s metropole[2] of

tight cities surrounded by

concentric circles of lesser

developed outer ring

villages, expanding outward

to the frontier. But to gain

insight into the western

expansion from the

perspective of pioneering

Americans, it is best to

turn the yellowed pages of a

primary text, in this case,

that of the History of

the Expedition under the

Command of Captains Lewis

and Clark. This text

provides a first person

narrative of the westward

travels of Lewis and Clark

and presents vivid

descriptions of the

environment and of the

natives they encounter.

Because the expedition was

assigned by the United

States government as a sort

of exploratory mission,

Lewis’ writing presents a

professionalized and

analytical perspective on

the environment and the

natives that inhabit it.

From the illustrative

narration of their

encounters with the natives,

Lewis and Clark seem to have

been a part of what Richard

White refers to as

“the middle ground”[3] of

the west, interacting with

the Native Americans in a

way that allowed for the

exchange of goods and

friendly hospitality. For

example, Lewis narrates an

occasion in which their

group was visited by several

natives upon which he

recalls, “we received them

kindly, smoked with them,

and gave them a piece of

tobacco to smoke with their

tribe…our two chiefs had

gone on in order to apprise

the tribes of our approach

and of our friendly

dispositions towards

them"[4]. The explorers were

cordial and welcoming in

cases such as this,

practicing the traditional

signs of peace and

friendship between

themselves and the Natives.

During their travels, Lewis

narrates their encounters

with the Indians, which are

seemingly friendly and

helpful interactions. Upon

meeting a tribe, for

example, the Lewis and Clark

group would honor the native

chiefs with presents and

would follow the practice of

smoking with the group as a

sign of friendship. Lewis

described the natives with

much detail and described to

great extent the differences

between each tribe they came

into contact with in regards

to physical countenance and

dress and the set up of

their villages. This is an

important note in regards to

the outlook of Lewis on the

natives. The natives were

not lumped into the broad

category of wild ‘savages’

but were instead studied in

regards to appearance,

language, health, diet, and

culture perhaps in a more

scientific and analytical

way than that of other

explorers who had different

intentions in their travels.

This may indicate a sort of

interest in the natives that

other frontiersman may not

have had. Lewis’ narrative

of his expedition offers the

perspective of the Captains

in regards to the frontier

and the movement west and

the exploration of both the

environment and the people

and cultures within it.

[1] Turner,

Frederick Jackson. “The

Significance of the

Frontier in American

History.” Report of

the American

Historical Association

for 1893. Pgs.

199-227 (AHA, 1893)

Return

to Top

|

|

Report of the exploring

expedition to the Rocky

Mountains in the year 1842,

and to

Oregon and North

California in the years

1843-44

- Nick

Schradle

In the mid-1840s,

the United States Congress

sponsored the first of

several expeditions into the

largely unexplored interior

of the United States. John

C. Frémont's Report

of the exploring expedition

to the Rocky Mountains in

the year 1842, and to Oregon

and North California in the

years 1843-44 details two of

these expeditions. The first

expedition commenced in

1842—following a western

course that would later be

known as the iconic Oregon

Trail—but stopped at the

South Pass of the Rocky

Mountains. The second

expedition, which lasted

from 1843-1844, followed the

same route but continued

into Oregon territory, then

circled Southward through

the Sierra Nevada into

California.

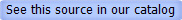

Frémont's

report consists of daily

journal entries which

recounted the day's

occurrences and also

recorded data such as

temperature, topography,

soil composition, geographic

coordinates, flora and

fauna, and various other

information. A number of

detailed illustrations,

mostly of impressive

landscapes, sporadically

accompany journal entries.

At the end of either

expedition's account are

extensive appendices

cataloging and expanding on

the data recorded in

Frémont's daily

entries.

Surprisingly, the majority

of the men in either of

Frémont's expeditions

were French-Canadian

“voyageurs.” The fact that

this introduced an

unnecessary language

complication to the

expeditions is at first

puzzling. However, it is

likely that these men had

valuable practical

experience with the frontier

in general and the interior

of the country in

particular—perhaps from

years spent trapping.

However, the extent of the

expeditions' collective

wisdom was at times

questionable. The expedition

of 1843-44 attempted to

cross the snow-bound Sierra

Nevada in the dead of

winter—despite clear

warnings from local Natives

to avoid such an

undertaking—and nearly

starved to death.

At the time of these

expeditions, the land west

and south of the Rocky

Mountains was still Mexican

territory. However, no

concern with or even

recognition of this apparent

(government sponsored)

incursion appears in

Frémont's accounts.

By the mid-century, the

territorial ambitions of the

United States accelerated

along with the ascension of

the ideology of Manifest

Destiny in American culture.

Frémont was a

harbinger of this powerful urge to

expand westward, an urge

that would lead to war with

Mexico only a few years

after the expeditions'

conclusion.

Frémont's encounters

with, and attitudes toward,

Native Americans on the

“frontier” is also

tragically indicative of

events and attitudes to

follow in the Indian Wars of

the mid-to-late 19th

century. The expeditions'

encounters with Natives were

almost always tense, and

usually balanced on the edge

of violence.

The gradual colonization of

the Eastern seaboard by

Euro-Americans began in the

16th century, immediately

impinging upon the

settlements of Native

Americans. Initially, a

“middle ground” developed

between Natives and

Euro-Americans that had

necessitated a degree of

cultural toleration and

political respect between

the two groups (see The

Middle Ground by Richard

White). However, this

gradually dissolved under

the consistent pressure

exerted by settlers on the

resources and land around

Native settlements. This

pressure had dire

consequences—disease and

warfare amongst Native

groups and between Natives

and settlers inevitably

decimated Native populations

and displaced Native groups

out of territory familiar to

them. By the mid 19th

century, existing

populations of Native

Americans also faced

considerable organized

discrimination from the

United States Government.

Most notably, the Indian

Removal Act of 1830 gave

President Andrew Jackson the

authority to forcibly remove

large populations of

Cherokee, Chickasaw,

Seminole, and Choctaw

Natives from the Deep South

and confine them to

relatively small territory

in present day Oklahoma.

The volatile nature of the

encounters between Native

groups and Frémont’s

expeditions was directly

related to the Natives’

displacement and conflict

with both settlers and those

in the employ of the U.S.

Government in the preceding

decades. Frémont,

however, does not display

cognizance of this fact or

sensitivity to the culture

or situation of Native

Americans. Incredibly, only

one man, and not Natives,

were killed in conflict with

Native groups over the

course of either expedition.

If at any point violence had

broken out on a larger

scale, Frémont and

his men were at a

considerable numerical

disadvantage and risked

annihilation. It is no

surprise that, despite the

ostensibly scientific aims

of the expedition, the

company carted an unwieldy

Howitzer canon over the

thousands of miles of rough

terrain. Tragically,

Frémont’s expedition

marked the beginning of the

U.S. Government’s

increasingly militant

expeditions into the

interior of the country.

These forays would

eventually escalate into the

Indian Wars of the mid to

late 19th century, in which

U.S. Army systematically

killed thousands of Native

Americans.

Return

to Top

|

|

History of the expedition

under the command of

Captains Lewis and Clarke,

to

the sources of the

Missouri, thence across

the Rocky Mountains and

down the River Columbia

to the Pacific Ocean.

Performed during the

years 1804-5-6. By order

of the government of the

United States Vol

I

- David Sena

"Orientals

in America"

Lewis and Clark in their

seminal 1804 expedition

found themselves in the

unique position of being a

stranger in a land that

now-Americans had known

about as part of a continent

that they had lived on for

more than 200 years.

Being one of the last

episodes of “first contact”

between Native Americans and

a Western power (in the form

of the new United States),

many of the same tendencies

towards “orientalism” that

had been present in earlier

contact zones of the 16th

and 17th centuries occurred

one more time in a way that

subtly persuaded many to

heed what had for years been

a siren call from the

West.

Meriwether Lewis

particularly as the

expedition’s “scribe” had a

great interest in conveying

the ebullient grandeur of

the land near the Missouri

River and its resources in

what he often described as a

“near paradise” (Lewis, 78)

full of great “abundance

with fish, game and tree of

all sorts” (Lewis, 78) that

stood in sharp contrast to

the settled and more stale

cityscapes which he came

from. Even when the

expedition was rough and

survival was not always

guaranteed, Lewis was

obsessed with meticulously

and mechanically describing

every aspect of his

environment in an effort to

try to understand all of its

inner workings, frequently

commenting on its “amazing”

peculiarities (all

throughout but here Lewis,

98). This fascination

with a new place of such

perceived magnificence and

treatment of it from the

perspective of a detached

and omniscient observer

engaging in empirical study

typifies one early way in

which Americans began to

take a sort of ownership of

the new frontier. In

believing in their ability

to understand a new

landscape and its mysteries,

the land can thus be

controlled and demonstrated

as being tamable.

These attitudes also

represent a voyeurism that

instantly whets the appetite

of any prospective pioneer

looking to engage with a

land of many fruits and

eccentricities and also

planted the seeds of later

imperialism.

Such mindsets even applied

to real human beings as

Lewis demonstrates through

the expedition’s dealings

with Native Americans in a

manner that severely though

subtly dehumanizes them

(though that was not

necessarily their conscious

reckoning). As

enthralled as he is with the

natural landscape, he is

just as captivated by the

“exotic nature” of Native

Americans (Lewis, 20).

He particularly sexualizes

Native American women,

taking great lengths in

detailing the way they dress

and how immodest they are

when it comes to wearing

revealing clothing. He

notes how the natives at one

village were all riddled

with venereal disease,

indicative to him of an

erotic and loosely

irresponsible people.

All Native Americans he

describes as being intrigued

by seemingly insignificant

and cheaply-made bronze

works like kettles and blue

beads which Lewis and Clark

were able to exchange for

needed food and

supplies. Both parties

thought they had got the

better deal from the

other. Although he

does not explicitly state

it, Native Americans seem to

Lewis like children who

engage in these “queer

behaviors” because they

simply do not know any

better way. This

orientalizing of an entire

race makes it very easy to

cast Native Americans as not

only undeveloped human

beings but also attracts

even more sentiment towards

settlement of the West in an

effort to observe and

possibly even engage in such

arousing and strange

activities independent of

government or constraining

society. Lewis

certainly felt he was being

impartial and frank, but his

underlying attitudes colored

his perspective and provided

the foundation for how the

United States viewed the

frontier as a place both

worth conquering and easy to

conquer.

Featured map:

This copy of a hand-drawn

map by expedition co-leader

William Clark, as objective

as it appears to be,

nevertheless hints at some

of Clark's

personal biases regarding the

land. From a top-down

perspective,

Clark intricately

details scores of natural

landmarks and

river routes giving

the land an

overwhelmingly abundant

feel. Yet from a

left-right perspective

the land is scaled to

seem far more compact

with the Pacific appearing

to be a much shorter

distance from Missouri

than as seen through

modern maps. The

Rocky Mountains themselves

appear to be an

afterthought. Perhaps

Clark intended

to depict a land full

of resources that is

nonetheless relatively easy

to traverse and quick to

travel through, a tempting

combination for prospective

settlers.

Return to Top

|

|

About

this Project / Acknowledgements

Occidental

College's "American Frontier"

Research Seminar was developed by

Dr. Jeremiah B.C. Axelrod, Adjunct

Assistant Professor of History.

The library project

is developed in collaboration with

the Special Collections

Department:

Dale Ann Stieber, Special

Collections Librarian

with student staff

Henry Boule and Claire Lem and

Laila Tootoonchi and Anahid

Yahjian.

Title Image:

Thomas Moran, "Nearing Camp,

Evening on the Upper Colorado

River, Wyoming, 1882," from

http://www.boltonmuseums.org.uk/collections/art/paintings_prints_and_drawings/oil/nearing_camp_moran

|

|

Page last edited on

03/12/2013.

Occidental

College Library Special

Collections & College Archives

© 2009 Occidental College

|

|

|

|

|