|

|

Table

of Contents

Explorations

of the West

Sam

Dalsheimer

Caitlin

Goss

Nick

Schradle

David Sena

Representations

of

Native Americans

Richard

Dybas

Amanda Leong

Cynthia

Robertson

The

Western Railroads

Ronni Toledo

Kayt

Fitzmorris

Jon Ingram

David

Halperin

The

California

Gold Rush

Jordan Helle

Adam

Lawrence

Marisa

Pulcrano

Patrick Ryan

California

as Western Destination/

Mediterranean Boosterism

Maddy

Kiefer

Danielle

Mantooth

Molly

Nelson

Stefanie Ramsay

Back

to Online Exhibits

|

Introduction

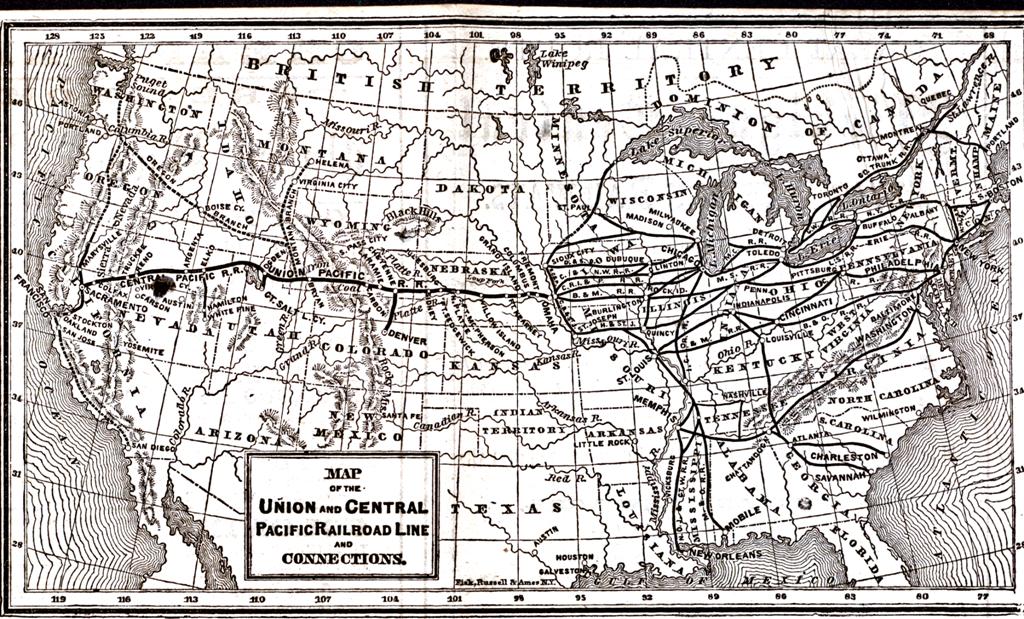

From initial surveys of the

territory upon which to build the

railroad to advertisements of new

regions accessible by the railroad,

our four texts outline the evolution

of American conceptions of the

frontier from the mid- to the

late-19th century. Volume XI of the

War Department’s Reports of

Explorations and Surveys of 1853

examines the land between the

Mississippi River and the Pacific

Ocean and the potential for a

cross-country railroad.[more]

Frederick Jackson Turner’s thesis on

the frontier likely stemmed from his

examination of such documents. The

surveyors’ accounts allude to the

frontier as a source of great

adventure in which developers could

help establish new regions by

conquering the savagery of nature.

The addition of such claims to the

Reports suggests an underlying

boosterism and potential for new

beginnings on the frontier. While

obviously written so as to persuade

the War Department to approve of the

construction of the railroads, the

ideas emphasized by the explorers

were later mimicked in

advertisements for the railroads.

Many parts of Crofutt’s

Trans-Continental Tourist Guide of

1871 stress the benefits of the

railroad as a corridor to the West

for pioneers to more easily access

and take control over land. In an

early incarnation of the modern

tourist guide, such claims embodied

America’s notion of “Manifest

Destiny,” of having a divine right

to expand across, and later beyond,

North America. This focus still

shows an extension of Turner’s

theories of the frontier. The

changes occurring out west, however,

can be seen in the depiction of the

far west as the ultimate

destination, rather than the central

territories and states.

Similarly, the Rand McNally’s Guide

to the Pacific Coast of 1893

promotes the West as an ideal

location for settlement which

enabled people to explore new,

entirely different worlds, even just

in traveling from one part of

California to another. While still

somewhat enthusiastic about

adventure, the perceived closing of

the frontier prompted railroad

companies and advertisers to place

less emphasis on the need to

“conquer” the land and more on the

benefits of living in the region.

Nonetheless, the opportunity to

settle in a new region still

portrayed the West, at least

implicitly, as a place to create new

lives and identities. Even when

traveling to unsettled lands, the

railroad became a corridor of

domesticity for which to travel

through foreign spaces.

As exemplified by portions of Health

and Pleasure on “America’s Greatest

Railroad”, railroad companies also

began representing relatively

unsettled areas as locations where

people could get closer to nature.

However, they no longer described

nature as a savage and dangerous,

and thus masculine, but rather as a

place in which people could be

psychologically and physically

rejuvenated. A more therapeutic

ethos took hold and claimed that

people “needed” temporary, rather

than permanent, sojourns to nature

to reduce stress and to renew their

tranquility. Despite a supposed

closing of the frontier, as Turner

stated in the same year that both

the McNally Guide and Health and

Pleasure were released, the railroad

supposedly enabled people to

simulate Turner’s challenges in

different ways to obtain similar

benefits.

|

|

Health and Pleasure on

"America's greatest

railroad":

Descriptive

of Summer Resorts and

Excursion Routes,

Embracing More Than One

Thousand Tours

- Ronni

Toledo

In the section on

American resorts in the

fifth issue of the

promotional series, Health

and Pleasure on “America’s

Greatest Railroad”, the New

York Central and Hudson

River Railroad Company

characterizes the Adirondack

Mountains as the “nation’s

pleasure ground and

sanitarium”. The description

of the region outlines the

myriad of benefits that the

New York wilderness confers

upon visitors; most

importantly, the opportunity

to unite with nature and be

restored to health and vigor

by the “soothing properties

of the balsamic air”[1]

After five pages of lofty,

detailed claims about the

beauty and value of the

region, the authors finally

express their true

intentions: to publicize the

opening of the Adirondack

and St. Lawrence Lines, two

of the only—and certainly

most convenient—ways to get

to the mountains and to

experience the tranquility

of the wilderness.

Published in 1893, the same

year that Turner delivered

his paper on the

significance of the

frontier, the part on the

Adirondacks agrees with

Turner’s description of the

frontier as a place where

man can escape the shackles

of civilization and return

to a more “basic state”. The

rest of the section,

however, offers a

representation of the

frontier that differs

significantly from Turner’s.

Turner suggests that the

frontier forces people to

abandon the metropole

entirely and to confront the

savagery of nature. Such a

process supposedly leads to

the creation of the American

identity since men must

learn to survive in a

completely different

environment. The Railroad

Company on the other hand,

merely encourages people to

take a temporary sojourn to

the Adirondacks; enough to

become reinvigorated, but

certainly not the length of

time required to form a

completely new identity.

Furthermore, while visitors

may acquire more strength

and individualism on their

short trips to the

Adirondacks, the Railroad

Company places much more

emphasis on the peacefulness

of the region and the

physical and mental

rejuvenation that the

mountains supposedly

provide, whereas Turner

assumes that man must face a

number of threats to his

existence on the frontier.

The Railroad Company may

have faced Turner’s frontier

while constructing the

lines, but their

advertisements for the lines

suggest that the railroad

transformed the region into

one of safety and beauty.

Ironically, the company

repeatedly claims that the

land upon which the lines

lay remains untouched and

untainted by human

intervention. The authors

essentially suggest that the

railroad enables Americans

to explore the regions that

Turner claims no longer

exist and to acquire

somewhat similar, if not

superior, benefits, while

avoiding “the fatigue and

hardships encountered in the

past”[2]

Notes:

[1] The New York Central

& Hudson River Railroad

Company,

Health and Pleasure on

"America's Greatest

Railroad": Descriptive of

Summer Resorts and Excursion

Routes, Embracing More Than

One Thousand Tours (New

York: New York Central &

Hudson River Railroad Co.,

1893), 114.

[2] Ibid., 115.

Return to Top

|

|

Reports of Explorations

and surveys:

to ascertain

the most practicable and

economical route for a

railroad from the

Mississippi River to the

Pacific Ocean. Made under

the direction of the

secretary of war, in 1853

- Kayt Fitzmorris

The

United States War Department

Reports of Explorations and

Surveys, Volume Eleven, was

created to “represent only

such portions” of the

western territories “as have

been actually explored, and

of which our information may

be considered reliable"[1]

in order to be reviewed by

the United States War

Department in preparation

for building railroads from

the East to the West.

Compilers of the reports,

Lieutenant G. K. Warren

especially, emphasized the

objective quality of

selecting explorers’

accounts, maps, and images

from which to form an

accurate account of the land

between the Mississippi

River and the Pacific Ocean.

In the collection are not

only topographical accounts

and maps, but also several

accounts of explorers’

experiences on the frontier.

Lieutenant Warren included

these accounts in order to

“promote the consultation of

the original reports and

maps, by pointing out to

each investigator those

works which probably contain

information about the region

of country especially

interesting to himself.”[2]

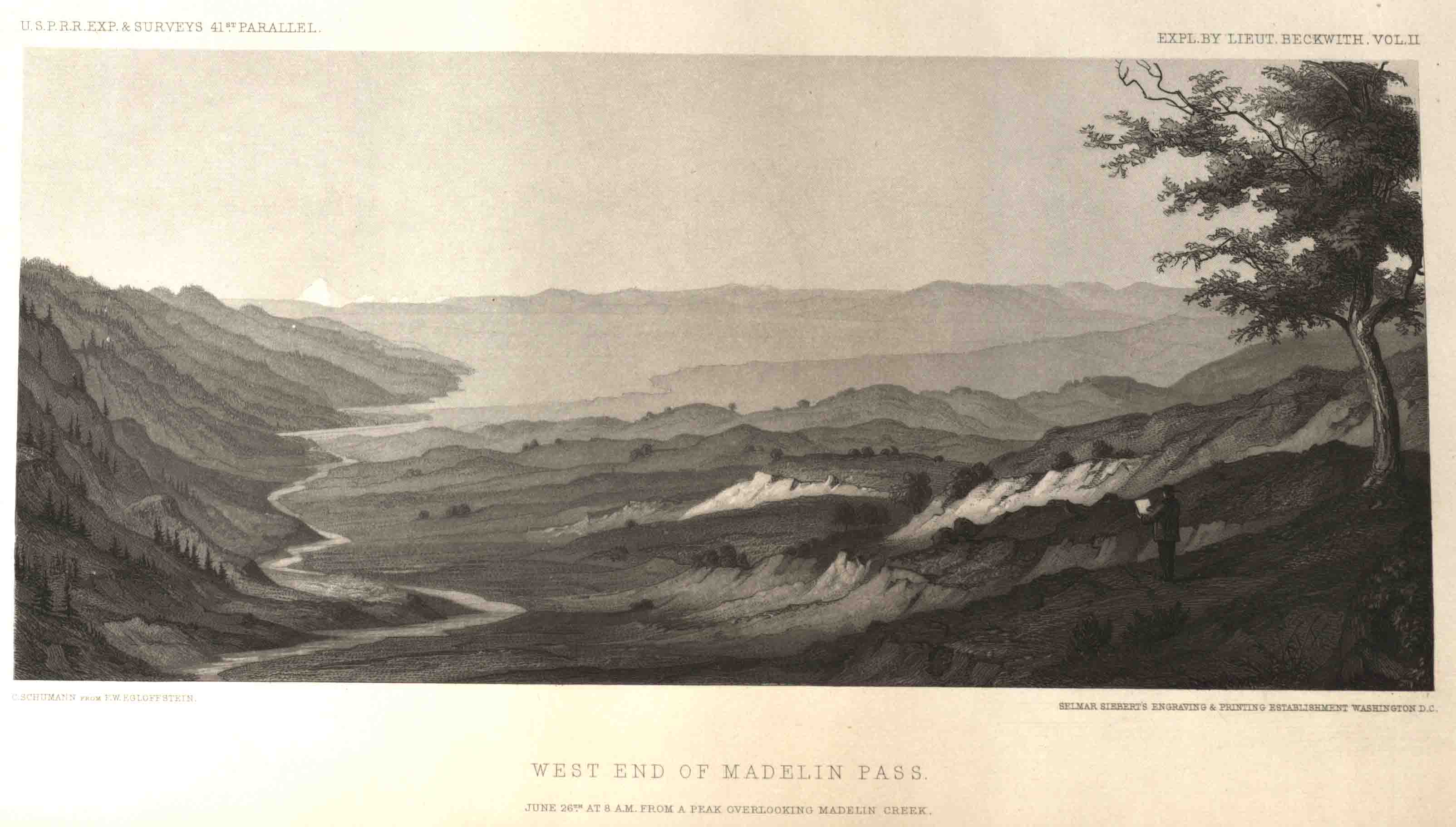

Despite his emphasis on

accuracy and objectivity

described in the beginning

of his introduction,

Lieutenant Warren also gives

value to the personal

accounts and biases that

come with exploring the

frontier. This subtle

boosterism for the territory

can also be seen in the

images included in the

volume. In several of the

detailed sketches of the

territory between the

Mississippi and the Pacific,

the foreground of the image

features people looking out

across the land. In some,

Indians survey the territory

while in repose. In others,

European explorers decorate

the foreground, eyeing the

undeveloped territory

confidently.

Lieutenant Warren’s report

accomplishes two things:

describing the territory in

preparation for the

cross-country railroad, and

highlighting the frontier as

a place of adventure and

beauty. His choice to

include accounts of American

explorers on the frontier is

reminiscent of Frederick

Jackson Turner’s belief that

a true American is a product

of his

surroundings—transformed by

the frontier after leaving

the east behind. In this

book the railroad presents,

although subtly, the

opportunities for developers

and builders to access this

wild frontier, becoming more

American as they travel

west.

Return

to Top

|

|

Crofutt’s

Trans-Continental

Tourist’s Guide

- Jon Ingram

The travel guide is

a portable book in which the

author gives detailed

information on the

trans-continental railroad.

Specifically, the text

focuses on the numerous

stations and stops along the

way, giving information

regarding them and the

surrounding area. This book

details not only what was

important to the writers of

the book, but what they

would have wanted people

traveling to know or what

was to be found along the

way. In this, the book

begins with descriptions of

western regions (Northeast,

Far West, etc) and gives

depictions of them and the

grandeur to be found.

Essentially, the book aims

to promote the railroad,

give incentive to travel

westward, and portray the

trans-continental as the

conduit to the west. The

second section of the text

gives a rather romanticized

version of how the rail line

came to be built, hearkening

back to the Civil War, and

showing the US in an

expansionist, nationalistic

light. The wording and

images indicate the heavy

prevalence of Manifest

Destiny that people still

felt at the time about the

frontier. In this light, the

Union Pacific railroad is

specifically mentioned. A

detailed history and summary

of its setup and the working

of the company is given as a

promotional review and

advertising can be found for

its railcars (particularly

the sleeper cars) as the

best options for travelers.

Much of these two sections

seem to revolve around the

tourism aspect of the guide,

using self promotion and

lofty descriptions to make

their points. Inserted into

this are detailed sketches

of the rail line, showing

the trains and the landscape

of the west, using them as

selling points and creating

the idea that the traveler

wants to be there looking

out at these areas from the

train.

Lastly, the

majority of the tourist

guide revolves around the

short summaries it contains

on the majority of station

stops along the way,

national parks, and features

of the landscape. What is

interesting is that while it

is classified as a

“tourist’s guide”, it does

not provide information for

the most part on what the

stops contain in the way of

food, lodging, or other

basics. Rather the train is

the focal point for these

necessities while the

landscape and what the train

passes through becomes the

focus. In a way, the

trans-continental at this

time is basically just a

corridor passing through the

frontier, but in the

descriptions we can see how

tourism will develop, such

as how Yellowstone is

referenced and how later

guides will include things

to do along the way. This

section is summed up by

category and alphabetical

order by the authors for

quick reference by page

number,in order that one

might quickly reference a

specific location. Ideally,

each description contains at

least several facts,

details, or points of

interest. For instance,

interesting occurrences,

land features, events, or

what the area specializes in

(cattle, grain). Every step

of the way is detailed with

tourist and factual

information with the

ultimate goal of California

being consistently present.

The theories of Fredrick

Jackson Turner are

consistent with this as the

West is shown as the escape

from the city. The west here

is the answer to improving

one’s life and forming a new

start, while everything

along the way is secondary

and just part of the

journey.

Return

to Top

|

|

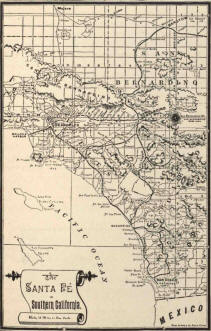

Rand, McNally & Co.'s

new guide to the Pacific

coast : Santa Fé

route: California,

Arizona, New Mexico,

Colorado, and Kansas

- David Halperin

Frederick Jackson

Turner describes the

American frontier as

“sharply distinguished from

the European frontier – a

fortified boundary line

running through dense

populations." [1] When it

comes to the history of the

western railroads in

California, one does begin

to see a noted boundary

line, yet the dense

population he spoke of did

not begin here, but rather

in Southern California. In Rand,

McNally & Co.’s Guide

to the Pacific Coast

(published during the same

year Turner delivered his

frontier speech), the

travel guide lists numerous

facts about the west,

stretching from Kansas to

California. Though the most

elaborate account of a

frontier-like state comes

when it describes the

junction at the small,

almost non-existent, town of

Needles, CA.

“Here,

the cars destined for Los

Angeles and San Diego turn

directly southward. It is

the end of the desert. By a

contrast and transition so

striking as to be almost

marvelous, you stand at this

lonely little desert station

almost upon the verge of a

country where all the

products of two zones grow

side by side, with a

luxuriance unknown elsewhere

on the globe, and beneath a

climate that within the past

five years has attracted

tens of thousands of

permanent residents." [2]

Clearly

this was a significant

landmark for both the

railroads and for western

migrants looking to

capitalize on a more

prosperous life in this new

and desirable climate.

Furthermore, though

California had existed as a

singular state since 1850,

there were increased

observations of the

differences between the

northern and southern

sections. When California

became a popular travel

destination the differences

noted between the two areas

allowed for a new,

Postcolonialist way of

identifying what

constitutes as foreign and

domestic. [3] This concept

is brought forth in the

travel guide book, which

explains that “Indeed it

may almost be said that

everybody, in California

or out of it, regards the

two sections as entirely

distinct…The distinction

has produced a ‘boom’ in

which the northern

three-fourths of the State

has not shared." [4] By

sending the trains all

across the state, the

respective populations

unquestionably developed

sharp contrasts to one

another as new groups such

as Los Angeles boosters

could now, for example, be

contrasted to northern

Californians with

different political

agendas.

In conclusion, the Rand,

McNally & Co. guidebook

serves not only to

physically map out the west,

but to encourage the curious

traveler to make the journey

to a rapidly expanding land.

As Richard Francaviglia duly

notes, “...maps are tools of

the spirited mind—the empire

builder and the storyteller:

they fuel the desire to

experience, even claim, the

geographic area that they

represent." [5]

The

guidebook clearly serves

to present nature and

the human response to

nature through the

railroad’s crossing of a

small, but mighty,

boundary in California.

[1] Turner,

Frederick Jackson. “The

Significance of the

Frontier in American

History.” American

Historical Association

(Washington DC) 1893.

(Page 3)

[2]

Steele, James W. Rand,

McNally & Co.'s

New Guide to the

Pacific Coast: Santa

Fé route:

California, Arizona,

New Mexico, Colorado,

and Kansas.

Chicago; and New

York: Rand, McNally

& Co., 1893, c1888.

(Pages 129-130)

[3] Axelrod,

R.B. & Axelrod,

J.B.C. Draft of

“Postcolonialism.” W.W.

Norton & Company,

Inc. 2004-2009. (Page

18)

[4] Steele,

James W. Rand,

McNally & Co.'s

New Guide to the

Pacific Coast: Santa

Fé route:

California, Arizona,

New Mexico, Colorado,

and Kansas.

Chicago; and New

York: Rand, McNally

& Co., 1893, c1888.

(Page 143)

Return to Top

|

|

About

this Project / Acknowledgements

Occidental

College's "American Frontier"

Research Seminar was developed by

Dr. Jeremiah B.C. Axelrod, Adjunct

Assistant Professor of History.

The library project

is developed in collaboration with

the Special Collections

Department:

Dale Ann Stieber, Special

Collections Librarian

with student staff

Henry Boule and Claire Lem and

Laila Tootoonchi and Anahid

Yahjian.

Title Image:

Thomas Moran, "Nearing Camp,

Evening on the Upper Colorado

River, Wyoming, 1882," from

http://www.boltonmuseums.org.uk/collections/art/paintings_prints_and_drawings/oil/nearing_camp_moran

|

|

Page last edited on 03/12/2013.

Occidental

College Library Special

Collections & College Archives

© 2009 Occidental College

|

|

|

|

|