|

|

Table

of Contents

Explorations

of the West

Sam

Dalsheimer

Caitlin

Goss

Nick

Schradle

David Sena

Representations

of

Native Americans

Richard

Dybas

Amanda Leong

Cynthia

Robertson

The

Western Railroads

Ronni Toledo

Kayt

Fitzmorris

Jon Ingram

David

Halperin

The

California

Gold Rush

Jordan Helle

Adam

Lawrence

Marisa

Pulcrano

Patrick Ryan

California

as Western Destination/

Mediterranean Boosterism

Maddy

Kiefer

Danielle

Mantooth

Molly

Nelson

Stefanie Ramsay

Back

to Online Exhibits

Back

to SC Landing Page

|

Introduction

The

California Gold Rush infused

images of opportunity and

individual glory to thousands of

prospectors traveling west,

creating an event that was

dictated more by fictitious ideas

of wealth than of the actual

possibility. For many, the event

helped solidify the possibilities

out west, as “the discovery of

gold, always an object of

ambition, has not infrequently

been prosecuted with eagerness and

avidity, and the wildest schemes

have been proposed to obtain these

coveted treasures” (Shuck, 1869).[more]

The hysteria created

by the Gold Rush, first

appearing in San Francisco and

then throughout the entire

state of California, reshaped

not only the region, but also

the entire country, something

Hubert Howe Bancroft describes

in the History of California

Volume XXIII. However, it was

the hysteria that produced

visions of widespread gold and

wealth, as the event itself

was short-lived and not nearly

as prosperous as it was

exaggerated to be out west.

This study will focus on defining

some of the key factors of the

Gold Rush, and use primary source

documents to detail the experience

of the event. The California

Scrapbook, written by Oscar T.

Shuck, examines the mining tools

used by prospectors during the

Gold Rush, emphasizing the

technological advances that

changed both the state of

California and the event itself.

The idea of “panning” for gold was

often viewed as the main form of

mining during the event, yet, in

reality, it was almost a complete

myth, exaggerated by the hysteria

caused by the event. Another key

factor during

the Gold Rush was the contact

zone between Native Americans

and prospectors. Frank Marryat

illustrates the relationship

between these two groups in

his book, Mountains and

Molehills. Prospectors often

treated these people as

bloodthirsty savages, a

treatment which Edward Said

would define as a clear

example of Orientalism, thus

allowing prospectors to obtain

powerful hegemony over these

indigenous people.

Furthermore, the lack of

government and political

institutions created an

emphasis on individuality in a

world of increasing crime,

which is expressed in The

Letters of Dame Shirley, by

Louise Amelia Knapp Smith

Clapp. This problem was a key

reason why settlements became

so dangerous, as the lack of

an organized society drove

prospectors to care little

about the ethics and laws of

society and thus, focus

entirely on individual ideals

of wealth.

The Gold Rush

impacted the not only the

country, but also the world,

as prospectors became so

engrossed with the idea of

wealth and glory that they

were willing to give up almost

anything in order to have a

shot at the “American Dream”.

The mythologies of the Gold

Rush provided people with an

unprecedented ambition; the

drive to obtain gold fueled

desires to obtain a lifestyle

that had the potential to be

incredible. While the Gold

Rush was often viewed as a

powerful antidote to withering

western expansion, its true

nature provided prospectors

with only dreams of wealth, as

almost everyone did not

“strike" it rich.

[i] Cabeza de

Vaca, Adventures in the Unknown

Interior of America, (New Mexico:

Crowell-Collier Publishing

Company, reprinted in 1983), p.63

[ii] Dame Shirley, California in

1851[-1852] ; the letters of Dame

Shirley, (San Francisco: The

Grabhorn Press, 1933), p. 120

[iii] Dame Shirley, California in

1851[-1852] ; the letters of Dame

Shirley, (San Francisco: The

Grabhorn Press, 1933), p. 122

|

|

History of California

Volume XXIII

- Jordan Helle

"California’s

Initial Reaction and

Hysteria to Discovery of

Gold"

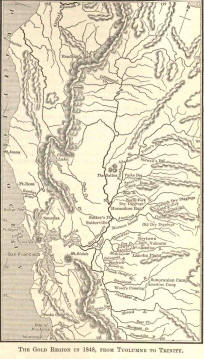

The quick and sudden

explosion that was the

California Gold Rush was the

substance of myth just as

much as fact. Chapter

IV in Bancroft’s

History of California Vol.

XXIII provides

excellent insight into the

madness that the discovery

of gold brought to

California in 1848, which

would lead to the mass

migration of gold seekers

from all corners of the

globe in 1849.

Initially, the first

discovery of the precious

metal did not create much

buzz at all. But after

a couple of months passed

and a few more found gold,

the rush was on and an

entire territory was

captivated.

Bancroft describes the

initial reaction to the

discovery of gold as filled

with skepticism, and not

even given much press in

local newspapers. However,

once a few more discoveries

were made, such as the one

by the Mormon leader Samuel

Brannan, people “were thrown

into a fever of excitement”.

[1] Bancroft used

Brannan’s discovery as an

example possibly because he

was a strong religious

leader and “man of God” who

held a lot of credibility,

increasing the likelihood

that people would start

believing there were

actually riches in the

hills.

San Franciscans now started

to believe, and many went as

far as immediately dropping

everything and just

leaving. They blazed

new trails, many after

selling everything they had.

[2] It is almost

unimaginable to think of the

atmosphere created by the

discovery of gold and

ensuing spread of news by

tall tales and word of

mouth. The fever that

Bancroft mentions sweeps San

Francisco completely as the

legend grows. Gold was

discovered in January and by

June three-fourths of the

male population had left for

the mountains in search of

riches they have only heard

of, leaving the city all but

abandoned. [3]

The hysteria was not

confined to just the city of

San Francisco, as soon all

of California had heard for

themselves. People

from all walks of life

figuratively dropped

everything and went as

“judges abandoned their

benches, doctors their

patients, soldiers fled

their posts, and criminals

slipped their fetters”. [4]

It was a sight to see as all

humanity left and gave up

their homes. The

landscape was suddenly

barren of human presence and

the “country seemed as if

smitten by a plague”. [5]

For miles and miles it would

have appeared as if all

humans had been wiped off

the face of the earth.

All of California was now

packed into the hills, as

widespread mythical tales of

gold and riches drew

them. Once there,

these fortune seekers took

to mining the hills in

search of the precious

metal. Soon to follow

was the rest of the country

and the world as the news of

gold would only continue to

spread and as the tale grew

taller. With the flood

of people whose sole purpose

was to search for wealth and

riches, there came an

atmosphere with little law

and justice.

[1] Hubert

Howe Bancroft, History

of California Volume XXIII

(San Francisco: History

Company, 1888), 56.

[2]

Bancroft, History of

California, 58.

[3] Ibid,

59.

[4]

Ibid, 62-63.

[5] Ibid, 63.

Return to Top

|

|

California Scrapbook

- Adam

Lawrence

The California Gold

Rush brought prospectors

from around the country in

search of wealth and a

desire to experience the

seemingly infinite

possibilities that the

region had to offer. As a

primary source, the

California Scrapbook,

complied by Oscar T. Shuck

in 1869, contains not only a

plethora of information

about the expansion and

history of the Gold Rush,

but also about the manner in

which this gold was found

and mined. Mining

technologies during the Gold

Rush paved the way for many

instrumental techniques that

built wealth and prosperity

in California, however, the

ideas of panning and

individuality within mining

were mere myths to the event

itself.

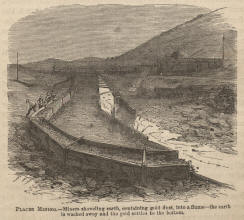

At

the start of the Gold Rush,

individualistic attitudes

coupled with a tremendous

quantity of gold brought the

desire to mine without any

delay nor complication. This

resulted in the development

of placer mining (also known

as panning for gold), which

involved shoveling the earth

for gold dust in sandbanks

looking for alluvial

deposits which could contain

the precious resource. Even

before the events before the

Gold Rush, “traders who

visited [California]

obtained small quantities of

gold dust from the earth in

the southern part of the

state” [1]. Although many

prospectors were attracted

to the simplicity and

immediate wealth of placer

mining, gold began to

diminish quickly in

quantity, and a more

collective process of mining

began to develop in Northern

California. During the

majority of the Gold Rush,

panning was rarely

utilized, yet it was a tool

used cherished by many,

including Frederick Jackson

Turner, to endorse and

celebrate the individuality

and possibility out on the

Frontier [2]. While

prospectors and westerners

saw visions of glorious

wealth in San Francisco, the

mining industry, which

helped dictate the influx of

wealth during the event, did

not share these emotions.

Within

a year after the first

finding of gold at Sutter’s

Mill, other forms of mining

were needed to reach veins

of pay dirt. Thus, hard-rock

mining and other forms of

hydraulic mining became

prominent tools to search

for these mineral deposits.

Shuck later notes that there

became not only a desire to

mine for gold, but also to

mine for other precious

minerals that stood in the

way of prospectors and

businessmen [3]. This often

drove prospectors to

carelessly mine in even the

heaviest banks of

sedimentary volume or on

lands of Native American

people (causing major

conflicts). Thus, after the

hysteria of placer mining,

mass mining became the only

reliable technique to

increase the quantity of

gold found in California,

diminishing the ideals of

individual fame and fortune

that the Gold Rush is often

associated with in a

positive light.

The

symbols of fortune and

prosperity that stem from

placer mining during the

Gold Rush often takes a

forefront in defining the

era as a whole. While the

notion that success and

opportunity awaited anyone

who traveled to California

during this time may have

been accurate within a span

of several months in 1848,

the Gold Rush was, in

reality, little more than a

myth, causing prospectors in

search of fame and glory to

fall back onto the mercies

of corporate mining moguls

who offered minuscule profit

for intense labor.

Return

to Top

|

|

California in 1851[-1852]

; the

letters of Dame Shirley

- Marisa

Pulcrano

"Justice

in the Gold Rush"

Frederick Jackson Turner’s

frontier was a place where

“savagery met civilization”,

where government

institutions were a foreign

concept and hierarchy was

inexistent, with populations

having “no chiefs [1],” as

explorers as far back as

Cabeza de Vaca discovered

with surprise. Similarly,

the societies created by the

California Gold Rush had

only a fragment of

government structure and

authority. Beginning on the

Overland trail, the

inherited power structure

was left behind, to be

replaced by the immigrants’

new and constantly evolving

relationships. However, the

Native Americans’

anti-proprietorship society

and the mining communities

diverged because of one

critical element: gold. This

material, which combined

natural and social

advantages and which

directly conferred great

fame and fortune, caused

primal desires to surface

and gave prospectors

something worth stealing and

fighting over. Louise Amelia

Knapp Smith Clapp describes

life at the gold mining

camps of mid-19th-century

California in The

Shirley Letters. Under

the pseudonym “Dame

Shirley,” she gained a

first-hand experience of the

opulence generated by the

Gold Rush at its beginning,

with the creation of a

flashy and rich mining town,

where gambling and drinking

the gold-dust away was a

constant occupation. When

one of the miners, Little

John, is convicted of gold

theft, Dame Shirley can’t

believe that “the last

person that would have been

suspected,”[2] was capable of

theft, which illustrates

just how strong a motive

gold was for even the most

innocent.

Enforcing

new, hierarchical rules on

the frontier was clearly

difficult. In the Gold Rush,

having left all familiar

structures behind,

individuals were free to

embody a new personality in

their quest for wealth and

other life opportunities.

The newly constituted

communities had to find ways

to deal with the increased

recklessness on the trail,

which meant instituting a

popular judicial system. In

Dame Shirley’s mining

community one encounters a

Squire, however he had a

lesser impact on judicial

decisions than did the

miners. In Little John’s

trial, a president and a

jury were elected from

amongst the miners, while

the Squire was allowed to

“play at judge sitting at

the side of their elected

magistrate,”[3]a task which

he docilely accepted. The

mob was ultimately

responsible for deciding to

hang Little John, which was

the sentence for most men

having stolen even small

amounts of gold. Turner

emphasized the positive

necessity for the

dismantling of power

structures on the frontier;

however Dame Shirley

illustrates the downsides of

lawlessness in a society

struggling to rebuild their

hierarchy. This schism was

due to gold, as it caused a

frontiersman to privilege

their individual desires for

wealth over the growth of

their society. The mythology

of the Gold Rush was a

powerful motive that could

turn any man or woman into a

thief, but one that also

generated a hierarchical

structure within the

frontier’s community.

[1]

Cabeza de Vaca, Adventures

in the Unknown Interior

of America, (New

Mexico: Crowell-Collier

Publishing Company,

reprinted in 1983), p.63

[2]

Dame Shirley,

California in

1851[-1852] ; the

letters of Dame

Shirley,

(San Francisco: The

Grabhorn Press, 1933), p.

120

[3]

Dame Shirley,

California in

1851[-1852] ; the

letters of Dame

Shirley,

(San Francisco: The

Grabhorn Press, 1933), p.

122

Return

to Top

|

|

Mountains and Molehills

- Patrick

Ryan

The Gold Rush in

California created a

frontier contact zone

between prospectors and the

native peoples of

California. Many people who

traveled west on the

overland trail seeking gold

were greatly concerned with

how to deal with the native

“savages”. The book Mountains

and Molehills is an

excellent primary source

document that explores the

interactions between the

Native American tribes of

California and the gold

prospectors.

The discovery of Gold in

California in 1848 drew

large numbers of people who

wanted to find wealth and

pursue the American dream.

The Native Peoples of

California were clearly

viewed by many prospectors

as a source of danger that

needed to be dealt with:

Indians--laboring

under the ridiculous notion

that anything can belong to

them that the white man

wants—become troublesome, it

is customary to drive them

back; but the Indians of

this regime when so driven,

will find their revenge in

carrying on an exterminating

warfare against the overland

emigration—at least so it

appears to me.[1]

The indigenous people of

California are viewed as a

bloodthirsty band of savages

who were driven solely by

greed for gold and for

anything else the

prospectors were after. The

author of this text clearly

believes that the Indians

have no right to own

property like white men do.

The most prevalent method of

dealing with native peoples

appears to be to drive them

away from any areas that

might contain gold or other

precious resources that the

whites desired. In reality,

the native peoples did not

pose a serious threat to

mining interests and were as

much a part of the mythology

of the Gold Rush as the

mythology of the frontier.

Furthermore, the author

accuses the natives of

“carrying on an

exterminating warfare”. The

hypocrisy of this assertion

cannot be overlooked in

light of the numerous

atrocities and genocides

that the United States

government perpetrated on

the indigenous peoples of

North America.

This account describing

perceptions of Native

Americans clearly comprises

what Edward Said termed an

“Orientalist Discourse” that

denigrates the natives of

California as nothing more

than animals driven only by

the desire for gold and

bloodshed. [2] Moreover, the

text implies that there is

no “Middle Ground”, as

defined by Richard White,

between the natives and the

prospectors because the

prospectors exert a clear

hegemony over the natives.

[3] The Indians are not

bargained or negotiated with

but are usually driven away

from mining areas by force

and many are moved onto

reservations by the U.S.

Government. This book’s

description of the frontier

seems to fit into Frederick

Jackson Turner’s framework

very well as the far west is

a place filled with violent

“savages” and a general

atmosphere of rampant

lawlessness. [4] The result

is a text that attempts to

justify the Gold Rush craze

as well as the blatant

disregard toward Native

American ownership of the

land.

Return to Top

|

|

About

this Project / Acknowledgements

Occidental

College's "American Frontier"

Research Seminar was developed by

Dr. Jeremiah B.C. Axelrod, Adjunct

Assistant Professor of History.

The library project

is developed in collaboration with

the Special Collections

Department:

Dale Ann Stieber, Special

Collections Librarian

with student staff

Henry Boule and Claire Lem and

Laila Tootoonchi and Anahid

Yahjian.

Title Image:

Thomas Moran, "Nearing Camp,

Evening on the Upper Colorado

River, Wyoming, 1882," from

http://www.boltonmuseums.org.uk/collections/art/paintings_prints_and_drawings/oil/nearing_camp_moran

|

|

Page last edited on 03/12/2013.

Occidental

College Library Special

Collections & College Archives

© 2009 Occidental College

|

|

|

|

|