|

|

Table of Contents

Home

Slavery

& Race

The South

Visual

Representations

Memorials

& Appropriations

Slavery

& Race

Sarah

Henderson

Joe Levell

Dan Haller

Nick

Schradle

The South

Dean DeChiaro

Steve Schaffer

Rick Ramirez

Visual

Representations

Alana Lemon

Jon Ingram

Peter Fúster

Aaron Stanton

Memorials

& Appropriation

Charles

Bennett

Molly Storer

Emma

Thorne-Christy

Other Online

Exhibits

|

The South

Introduction

The exploration texts of

Jefferson Davis, Edward A.

Pollard, and Francis Wilson

demonstrate a large array of

southern remembrance and

sentiments of the Civil War and

President Lincoln. In these

texts there is an increasing

tone of justification of

southerner rebellion as well as

swaying the war in favor of the

confederacy.[more]

In

The Rise and Fall of the

Confederate Government Davis concludes

that Lincoln and the federal

government were nothing more

than tyrants and the

confederacy was merely

exercising its

constitutional rights.

Similarly,

former

Richmond

Examiner publisher Edward

A. Pollard runs on the

foundation President Davis

laid out and attempts to

objectively re-write the

history of the war from a

Southern perspective. While

attempting to redirect

public memory of the South

throughout the novel,

Pollard went as far as to

say that Gettysburg was a

victory for the South.

Pollard also strategically

omits any mention of

President Lincoln’s

assassination.

Finally,

Francis Wilson provides a

face and back-story to

Lincoln’s killer, John

Wilkes Booth. Leading with a

Booth quote, “Our country

owed all her troubles to

him, and God simply made me

the instrument of his

punishment"[1], Wilson

identifies Booth as a “Lost

Cause” fanatic. Wilson

believes that Booth was a

spotlight-seeking assassin

who thought he would become

a staple in Southerners

memory of the Civil War.

These three

prime examples of the

south’s memory of the Civil

War and Lincoln, display a

common theme of southern

moral victory in the face of

a great tyrant. This view

helped many veterans and

natives of the South to

rationalize the war’s

outcome and the post war

era.

These examples

can also certainly be paired

with David W. Blight’s

Race and

Reunion, in which the

author touches on the

tradition of the Lost Cause

and how reconciliation could

stem from the Southern

ideology by separating

slavery from the cause of

the Civil War. Blight

recalls a speech given by

Robert E. Lee’s grandson

delivered in 1911, where he

suggested, “If the South had

been heeded, slavery would

have been eliminated years

before it was. It was the

votes of the southern states

which finally freed the

slaves.” [2] By twisting the

history and using this

strange logic, Lost Cause

believers could not be

absolved from the

responsibility of slavery

but also made them the true

abolitionists. As Blight put

it, “protected by such mists

of sentiment, the past could

be anything people wished.”

[3] Finally, the notion

created by Lost Cause

members stressed that even

when Americans lose, they

win. This indomitable

spirit, that Margaret

Mitchell infused into her

character Scarlett O’Hara in

Gone with the

Wind

(1936), and

such is the basis of the

enduring legend of Robert E.

Lee—through noble

character, he won by losing.

[4]

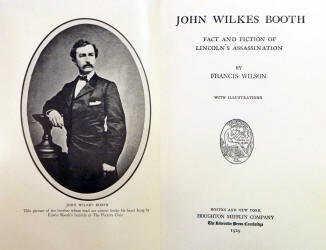

[1] Wilson, Francis.

John

Wilkes Booth: Fact and Fiction

of Lincoln's Assassination, 1st

ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin,

1929. pg. xv.

[2] Blight, David W.

Race

and Reunion,

The

Civil War in American Memory.

Harvard

University Press, 2001. pg.

283.

[3] Ibid., pp. 283.

[4] Ibid., pp. 284.

|

|

Wilson,

Francis. John Wilkes

Booth: Fact and Fiction of

Lincoln's Assassination Wilson,

Francis. John Wilkes

Booth: Fact and Fiction of

Lincoln's Assassination

1st ed. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin, 1929

-

Dean DeChiaro

It does not

take long to gather the

gist of Francis Wilson’s

John Wilkes

Booth: Fact and Fiction of

Lincoln's Assassination. The author

dedicates the volume to

Booth’s mother, Mary, whom

he writes suffered from

“unfathomable anguish”

following the night of

Lincoln’s death, which

brought “a pall of inky

blackness, and [spread]

sorrow everywhere”

(Wilson, vii). Wilson

provides a predictably

critical overview of

Booth’s life, tracing his

successful career as a

well-respected actor, his

downward spiral into Lost

Cause fanaticism, the

assassination, and finally

his miserable death in a

tobacco barn outside Port

Royal, VA. Wilson credits

Booth’s ambition to kill

Lincoln to a “morbid

thirst for notoriety” and

decries the soldier who

shot him for sparing Booth

“the disgrace of dying

like a criminal on the

gallows” (Wilson, 136,

180). Other accounts of

Lincoln’s assassinations

written during the

post-war period by

Wilson’s Northern

contemporaries,

unsurprisingly, usually

take the same opinion of

Booth.

Interestingly, despite the

fact that Wilson’s book

was published in Boston,

it presents an opinion of

Booth that would have been

found in Southern produced

books on the

assassination. In line

with Lost Cause ideology,

Southern sentiment towards

Booth was surprisingly

low. Had Lincoln lived to

serve through the

Reconstruction era, they

believed, the South would

have been treated with far

more lenience. Booth’s

fanatic blunder destroyed

any possibility of that

happening. Wilson’s Booth,

therefore, endures the

same hatred from both the

North and the South,

albeit for different

reasons.

Click

on Image

for Larger View

Return

to Top

|

|

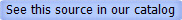

Pollard,

Edward A. The Lost

Cause: A New Southern

History of the War of the

Confederates New York: E.B.

Treat & Co., 1866.

-

Steve

Schaffer

Edward A.

Pollard’s book looks at

the war between the states

from a decidedly Southern

point of view. He condemns

previous works about the

war and states, “the facts

of the War of the

Confederates in America

have been at the mercy of

many temporary agents;

they have been either

confounded with

sensational rumours or

discoloured by violent

prejudice: in this

condition they are not

only not History, but

false schools of public

opinion" (Pollard, 1). The

entire war is covered from

Fort Sumter to Appomattox.

Published just after the

war, it gives us a look

into what Southern

contemporaries thought of

the war and the Presidents

of each side. Pollard

promises in the foreword

that his latest rehashing

of the momentous events of

1861-65 would be free of

political slander and

would present fact rather

than opinion. Despite this

claim, Pollard falters

with his vow and loses

much objectivity, for

example, by claiming

Gettysburg was a victory

for the south. Pollard’s

tone of readdressing the

remembrance of fallen

Southern soldiers is very

similar to that described

in Drew Gaulpin Faust’s

study The Republic of

Suffering,

when she quotes President

McKinley’s 1898 speech in

Atlanta that “these heroic

dead” had in the preceding

year risked their lives in

the great war; “the brave

Confederates should be

officially honored

alongside their Union

counterparts.” [1] All of

this is of course

Reconciliation discourse

by putting the Civil war

behind the United States

and creating a sense of

nationalism among sections

that, up to 1865, had been

bitter enemies. This book

in itself is also a prime

example of the Lost Cause

discourse.

Throughout the

book, Pollard refuses to

acknowledge the US as a

national entity he instead

justifies Southern

secession based on the

idea that some inhabitants

of the pre-United States

British colonies

considered each state a

sovereign nation.

Remarkably, Pollard makes

little mention of slavery

and completely avoids any

mention of Lincoln’s

assassination.

[1]

Faust, Drew

Gilpin. This Republic of

Suffering: Death and the

American Civil War. New

York: Knopf, 2008.

pg. 269.

Click

on Image

for Larger View

Return to Top

|

|

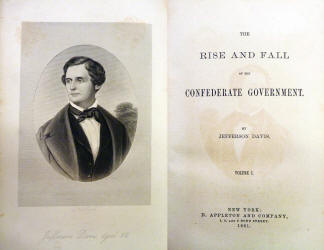

Davis,

Jefferson.

The Rise and

Fall of the Confederate

Government Davis,

Jefferson.

The Rise and

Fall of the Confederate

Government

New York: D.

Appleton and Co., 1881

-

Rick Ramirez

Following the

Civil War, the President

of the former Confederacy

Jefferson Davis spent a

few years researching and

writing for this work. The

objective of Davis is to

“show that the Southern

States had rightfully the

power to withdraw from a

Union into which they had,

as sovereign communities,

voluntarily entered"

(Davis, iv). In order to

substantiate this

argument, Davis writes a

two-volume work with

historical information

regarding the foundation

of the constitution, the

establishment of the

Confederacy, and various

legal and constitutional

precedents. Davis uniquely

demonstrates a strong

understanding of the

Constitution providing an

extremely insightful

constitutional analysis.

As a result, he advances

the Southern belief that

the “war waged by the

Federal Government against

the seceding States was in

disregard of the

limitations of the

Constitution and

destructive of the

principles of the

Declaration of

Independence” (Davis, iv).

Ultimately, through the

analysis of Davis, the

work argues the actions of

the Federal Government and

Lincoln were

unconstitutional and

tyrannical.

Click

on Image

for Larger View

Return to Top

|

|

| |

About

this Project / Acknowledgements

Occidental

College's "Lincoln Legacies"

Research Seminar was developed by

Dr. Jeremiah B.C. Axelrod, Adjunct

Assistant Professor of History.

The library project

is developed in collaboration with

the Special Collections

Department:

Dale Ann Stieber, Special

Collections Librarian with student

staff

Alana Lemon and Brittany Todd.

Main graphic

images:

|

Page last edited on 03/12/2013.

Occidental

College Library Special

Collections & College Archives

© 2010 Occidental College

|

|

|

|

|

|