|

|

Table

of Contents

Home

Slavery

& Race

The South

Visual

Representations

Memorials

& Appropriations

Slavery

& Race

Sarah

Henderson

Joe Levell

Dan Haller

Nick

Schradle

The South

Dean DeChiaro

Steve Schaffer

Rick Ramirez

Visual

Representations

Alana Lemon

Jon Ingram

Peter Fúster

Aaron Stanton

Memorials

& Appropriation

Charles

Bennett

Molly Storer

Emma

Thorne-Christy

Other Online

Exhibits

|

Slavery & Race

Introduction

In the wake of the Civil

War, the ideology of

reconciliation stressed the

similarities between the North

and South while ignoring the

underlying issues that caused

the conflict. The following

documents were all written in

the twentieth Century, and

qualify as retrospective

evaluations of slavery and race

as they pertain to President

Lincoln. [more]

These documents offer a

diverse collection of

perspectives on the status of

African Americans during and

after the Civil War. Although

Lincoln’s true feelings

regarding the issue of slavery

controversial, there is clear

evidence of an evolution in

Lincoln’s views of slavery and

race over time. Each of the

authors emphasize different

stages in the evolution of

Lincoln’s views in order to

frame their own particular

arguments about the role of race

in American society. Due to this

variance, all of these documents

pose at least partially — and

sometimes completely —

conflicting accounts of

Lincoln’s attitude toward

African Americans.

Only one of the documents,

written by white supremacist

Earnest Cox, completely embodies

the ideal of reconciliation. Cox

does so by fixating on the

evidence of Lincoln's preference

for the colonization of African

Americans during the first years

of his presidency— a racist

sentiment that undermines the

legacy of emancipation and

bolsters the conciliatory idea

that the war was fought

primarily in order to uphold the

Union. The other documents

engage and contradict this

ideology. Another white

supremacist, Neo-Confederate

Giles B. Cook, argues that

Lincoln's motivation for

emancipation stems from his

aspirations for personal glory.

This sentiment undermines

Lincoln’s legacy but does not

truly embody the spirit of

reconciliation. The other

documents directly challenge

reconciliation by focusing on

the legacy of emancipation and

expressing Lincoln’s centrality

in its deliverance. In the

pamphlet “The Slavery Atmosphere

of Lincoln’s Youth,” Louis A.

Warren argues that the

anti-slavery social climate of

Kentucky, and Lincoln’s personal

encounters with slavery in

adolescence, engendered his

empathy for the plight of slaves

and culminated in the

Emancipation Proclamation.

Finally, African American

scholar Robert Moton’s pamphlet,

“The Negro's Debt to Lincoln,”

emphasizes Lincoln’s role as the

Great Emancipator of the

African-American people. While

American culture was tempted by

reconciliation in the decades

following Reconstruction, these

documents show that disparate

ideologies grounded in

egalitarianism and white

supremacy challenged this

dominant ideology.

|

|

Cox,

Earnest Sevier. Lincoln’s

Negro Policy.

Richmond, Va.: The

William Byrd Press. 1938.

-

Sarah

Henderson

Earnest Sevier

Cox was a committed white

supremacist who published

Lincoln’s Negro Policy

to portray the theme of

colonization. Cox examines

both Lincoln’s abolition

of slavery and

colonization efforts. This

pamphlet examines a period

of time, the late 1930s,

when the question of negro

repatriation was presented

to congress for the first

time since Lincoln’s

death. The idea of

repatriation sparked Cox’s

interest, and he begins by

explaining that in his

opinion Lincoln was

“classed as the

outstanding advocate of

the cause of Negro

colonization” (Cox, 6).

Cox writes that for every

solution Lincoln

considered for the slavery

problem, the idea always

fell back on colonization.

Cox depicts Lincoln in a

positive light, explaining

that he gathered Negros

together to emphasize the

peaceful and voluntary

separation of the races.

Additionally, Cox

discusses that Lincoln

offered Federal aid to any

African Americans that

would volunteer for

colonization.

When

discussing the treatment

of African Americans

after emancipation and

the idea of the lost

cause, Cox uses

similar techniques to

those described in David

Blight’s Race and

Reunion

[1] . Cox shares similar

opinions to Jefferson

Davis regarding the

treatment of African

Americans after the

emancipation

proclamation. Cox argues

that in both the North

and South there was an

unwillingness to give

the Negro a nation of

his own. Cox uses his

piece not only to show

his Southern views, but

to depict his idea of

truth in the North.

Although Cox is able to

use quotes from Lincoln

to show that at some

point Lincoln agreed

with colonization, there

is no solid evidence

that this was the case

after 1863.

[1] Blight,

David W.

Race and

Reunion.

Cambridge:

Harvard University

Press, 2001.

Click

on Image

for Larger View

Return to

Top

|

|

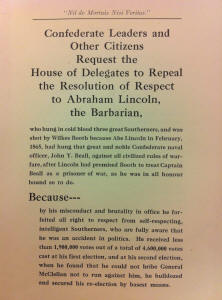

Cook,

Giles B. et al. “Confederate

Leaders and Other Citizens

Request the House of

Delegates to Repeal the

Resolution of Respect to

Abraham Lincoln, the

Barbarian... ” Cook,

Giles B. et al. “Confederate

Leaders and Other Citizens

Request the House of

Delegates to Repeal the

Resolution of Respect to

Abraham Lincoln, the

Barbarian... ”

1928. Pg 6-8.

-

Joe Levell

The

Confederate and white

supremacist argument

regarding slavery offers an

opinion that is far from the

popular image of Lincoln the

gracious emancipator. Known

as ‘the lost cause

argument,’ Confederate

members deny the critical

nature of slavery to the war

and depict Lincoln as a war

mongerer rather than a

national hero. David Blight

explains the lost cause by

saying it “took root in a

Southern culture awash in an

admixture of physical

destruction, the

psychological trauma of

defeat, a Democratic Party

resisting Reconstruction,

racial violence and with

time, an abiding

sentimentalism” [1]. The

Confederate memory became a

defense of Southern war

aims, turning the South’s

identity from racist

slaveholders to oppressed

patriots.

This

pamphlet includes letters

to politicians and an

biography of Lincoln.

Written in the twentieth

century, it offers an

interpretation of the war

that has developed over

time rather than an

instinctive reaction.

G.W.B. Hale, author of “A

Concise Life of Abraham

Lincoln and the Memorial

Act of Lincoln Passed by

the House of Delegates of

Virginia,” suggests that

“while pretentiously

claiming that slavery and

the Union were the main

factors that impelled the

war on the States, the

real inwardness of the

instigators of that war

was to perpetuate the

Republican party”

(Cook, 6). Instead of

suggesting one of the main

factors of the war was

both slavery and the

preservation of the union,

Hale argues that it

was purely political. By

splitting the war’s moral

and political roots,

Lincoln comes across as a

ambitious and arrogant

President who put

Presidential glory before

the best interests of the

population. By heavily

focusing on Lincoln’s lack

of religion, Hale argues

that the consequential

lack of Christian morality

proves Lincoln could not

have been the true savior

of the slaves. “Lincoln

did not save the Union as

it was (as our forefathers

made it) but only the

Republican party. He

defeated the South and

trampled under foot the

Constitution of the United

States in doing so” (Cook,

8). Lincoln, by freeing

the slaves, only

maintained the power and

status of the Republican

and destroyed the balance

of power in the South.

Such an argument is key to

the Southern white

supremacist view and

denies the South’s loyalty

to slavery, a role that

caused the biggest split

within American society.

[1] Blight,

David W.

Race and

Reunion.

Cambridge:

Harvard University

Press, 2001.

Click

on Image

for Larger View

Return to Top

|

|

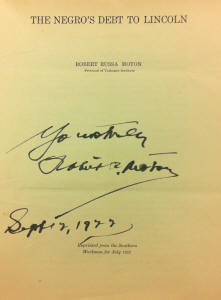

Moton,

Robert Russa

“The Negro’s Debt to

Lincoln”

1922

-

Dan Haller

On May 30th,

1922 the Lincoln Memorial

was officially dedicated

and opened to the public

in Washington, D.C. Robert

Russa Moton, then the

Principal of the Tuskegee

Institute, delivered one

of the addresses. Moton,

who succeeded Booker T.

Washington as the head of

Tuskegee after

Washington’s death in

1915, was the only

African-American invited

to speak at the event.

While other

speeches given during the

dedication ceremony

celebrated Abraham

Lincoln's preservation of

the Union, Moton chooses

to celebrate Lincoln in a

way that had been nearly

forgotten by the 1920’s:

Lincoln as the “Great

Emancipator.” It is

obvious that for Moton,

and for most

African-Americans,

Lincoln’s greatness

resided in the fact that

he “spoke the word that

gave freedom to a race,

and vindicated the honor

of a nation conceived in

liberty and dedicated to

the proposition that all

men are created equal”

(Moton, 5). Rather than

speculating on what

Lincoln thought about

slavery and race, Moton

emphasizes the fact that

at the bleakest moment in

the history of the nation

Lincoln chose to fight for

the “common humanity” of

all men. Moton casts

Lincoln into the role of a

messiah who gave his life

so that all the people in

the Union could enjoy

equal opportunity and

freedom. Thus all men,

Black as well as White,

owe a great debt to

Lincoln.

The ideas expressed by

Moton parallel much of our

readings that cast Lincoln

as the “Great Emancipator”

and the Martyr who gave

his life to save the

nation. In Sarah Vowell’s

Assassination

Vacation,

we find a sentiment that

is very similar to the one

expressed by Moton.

Vowell’s empasized that,

whether or not Lincoln

originally planned to end

slavery from the start,

that is precisely what he

did [1]. For Vowell

as well as Moton,

Emancipation itself is the

legacy for which Lincoln

should be most celebrated.

It was his ability

to feel empathy to those

bonded in servitude, and

the fact that Lincoln

ultimately died for what

he believed in, that

continues to cement his

place in American History.

[1]

Vowell, Sarah. Assassination

Vacation. Simon and

Schuster, 2005. Pg 36.

Click

on Image

for Larger View

Return to Top

|

|

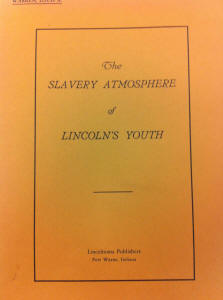

Warren, Louis A.

The Slavery Atmosphere of

Lincoln's Youth

Fort Wayne:

Lincolniana Publishers.

1933. Pg

4-9.

- Nick

Schradle

In 1933, on

the 70th anniversary of

the signing of the

Emancipation Proclamation,

the director of the

Lincoln National Life

Foundation Louis A. Warren

penned the pamphlet “The

Slavery Atmosphere of

Lincoln's Youth.” This

small, fourteen page

document posits new

historical evidence about

Lincoln's early life and

questions part of Lincoln

historiography.

Specifically, Warren

defends Lincoln's legacy

from critics who, he

perceives, doubt the moral

intentions behind the

release of the

Emancipation Proclamation.

Warren's pamphlet offers a

broad array of

circumstantial evidence,

as well as pure

speculation, that frames

Lincoln's experiences in

childhood and adolescence

as integral to his

presumed early moral

opposition to slavery, and

ultimately his issuance of

the Emancipation

Proclamation. In his book

Race and Reunion,

David W. Blight

argues that the Lost Cause

discourse, an occlusion in

the South's collective

memory about the origins

of and justifications for

the Civil War, undermined

the significance of

emancipation. This

discourse sought to deny

the legacy of

emancipation—which for

many, provided the

ultimate justification for

the Union war effort—by

recasting slavery as a

benevolent institution for

its African American

subjects. [1] Warren's

purpose is to defend the

legacy of the Emancipation

Proclamation by

constructing an argument

implicitly supporting

Lincoln's personal reasons

for issuing the

declaration.

Louis Warren's argument is

presented chronologically

over a broad temporal

scope. The first argument

in this chronology details

the existence of strong

anti-slavery elements in

the slave state of

Kentucky, extending back

to the childhood of

Lincoln's parents. Warren

offers circumstantial

evidence, collected from

the records of several

anti-slavery Baptist

congregations, that Thomas

and Nancy Lincoln may have

imparted anti-slavery

views, originating from

their own childhoods, on

the young future president

(Warren, 4).

Warren's second argument

focuses on the controversy

of slavery during

Lincoln's childhood in

Hardin County, Kentucky.

He notes that young

Abraham and his family

attended Little Mount

Church, a congregation

headed by the avowedly

anti-slavery Baptist

preacher, David Elkins

(Warren, 8).

To bolster his

argument, Warren includes

several letters written by

President Lincoln in

correspondence with

colleagues and friends, in

which the President makes

general reflections about

his early aversion to

slavery. Engaging in a bit

of historiography, he

admonishes (in)famous

Lincoln biographer William

Herndon for downplaying

these circumstances in

shaping Lincoln's moral

opposition to slavery

(Warren, 8).

Warren posits that

Lincoln's first, and

presumably negative,

encounter with slavery as

an adolescent probably

occurred along Cumberland

Road—a main thoroughfare

for the slave trade

between Louisville,

Kentucky with Nashville,

Tennessee (Warren, 9).

Finally, Warren identifies

the Lincoln family's move

to Indiana, and young

Abraham Lincoln's

subsequent experience with

slavery while taking a

river boat to New Orleans,

as another key factor

concretizing his early

anti-slavery beliefs.

This

document should be viewed

in light of the

increasingly pervasive

rhetoric in the decades

following Reconstruction

of the South's “Lost

Cause,” which sought to

exclude slavery and race

as factors contributing to

the Civil War. This

pamphlet is an attempt,

with the limited evidence

available to its author

Louis Warren, to

reemphasize the

significance of

emancipation by

legitimizing the budding

moral sentiments and early

emotional experiences of

the Emancipation

Proclamation's storied

author.

[1] Blight,

David W. Race and Reunion.

Cambridge:

Harvard University Press,

2001. Pg. 344-345.

Click

on Image

for Larger View

Return to Top

|

|

| |

About

this Project / Acknowledgements

Occidental

College's "Lincoln Legacies"

Research Seminar was developed by

Dr. Jeremiah B.C. Axelrod, Adjunct

Assistant Professor of History.

The library project

is developed in collaboration with

the Special Collections

Department:

Dale Ann Stieber, Special

Collections Librarian with student

staff

Alana Lemon and Brittany Todd.

Main graphic

images:

|

|

Page last edited on 03/12/2013.

Occidental

College Library Special

Collections & College Archives

© 2010 Occidental College

|

|

|

|

|

|