|

|

Table

of Contents

Explorations

of the West

Sam

Dalsheimer

Caitlin

Goss

Nick

Schradle

David Sena

Representations

of

Native Americans

Richard

Dybas

Amanda Leong

Cynthia

Robertson

The

Western Railroads

Ronni Toledo

Kayt

Fitzmorris

Jon Ingram

David

Halperin

The

California

Gold Rush

Jordan Helle

Adam

Lawrence

Marisa

Pulcrano

Patrick Ryan

California

as Western Destination/

Mediterranean Boosterism

Maddy Kiefer

Danielle

Mantooth

Molly

Nelson

Stefanie Ramsay

Other Online

Exhibits

|

Introduction

Beginning in

the late nineteenth century,

boosters marketed Southern

California to residents of other

states, purporting it to be a land

of permanent vacation. Americans

from the Midwest and the East were

encouraged first to visit the

wonderful land of California, and

then eventually make permanent

residence there. Charles F. Lummis

edited two magazines that

beautifully illustrate the ethos

of the culture of boosterism.[more]

Land

of Sunshine and Out West

provided ready-made examples

of the good life in California.

Particularly interesting is the

postcard provided by Land of

Sunshine that could be sent

to friends and families back home

along with a subscription to the

magazine. Lummis urged newly

transplanted Californians to

spread the message of boosterism

to their Eastern friends by

saying, “You have not forgotten

them – the people you grew up with

back in Ohio, or New York… they

often speak of you and say, ‘He is

out in Southern California now,

making money hand over fist. Lucky

fellow! I wish I were there.’”

(13) Such blatant promotion is

rampant in these magazines. The

focus of this strategy was

centered around several themes.

These include quality of climate,

abundance of agriculture,

romanticization of California’s

mission history, and the real

estate boom of Hollywood. The

following essays discuss these

aspects of California boosterism

in more depth.

Lummis, Charles F. Land of

Sunshine. Land of Sunshine

Publishing Co., June

1894: 13.

|

|

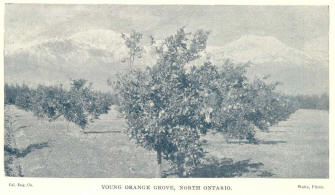

Land of Sunshine,

article: “The Orange in

Southern California” –

Volume II, No. 4, March

1894

- Maddy

Kiefer

Horace

Edwards’ article, “The

Orange in Southern

California,” boasts the

extreme success of the

orange in the Golden State,

attempting to prove to the

rest of the country that

this seemingly insignificant

attribute was reason enough

to relocate to California.

He explains that

“Orange-growing is

undoubtedly the most

important horticultural

industry in Southern

California,” and describes

it as the “undisputed king”

of the agriculture industry

(Edwards, 67). He appeals to

easterners by insisting

that, “To those brought up

in the bleak and wintry

East, orange-growing has

always a deep fascination,”

and that they find no

greater joy than when they

have the chance to visit a

California orange grove

(Edwards, 67). Easterners

frequently express a desire

“to pick an orange from the

tree ‘with their own

hands,’” as there is no

other fruit with “such a

halo of romance” (Edwards,

67).

When reading advertisements

in Land of Sunshine, it is

apparent that the various

ads were generated to appeal

to different demographics,

each of them presenting

varying aspects of the

culture and opportunities

that California provided.

The agricultural aspect,

seen in this article, is

appealing to many Midwestern

farmers, reassuring them

that they could continue

their farming work even out

west, and romanticizing the

experience of having an

orange grove. In contrast,

other ads and articles boost

the civilization and

metropolis that can be found

in California.

However, many of these

advertisements are

misleading. This article

fails to mention

California’s largely

engineered environment, and

only briefly points out that

oranges, despite not being

native to the state, can

only grow there because of

the engineering of the land

(Edwards, 67). It also

doesn’t mention the

remoteness of Los Angeles

from the rest of American

civilization – once

Midwesterners would move

that far west, they would

seldom be able to go back

home, and they would be in a

large region that had few

developed cities.

Horace Edwards briefly

mentions the lack of

accessible water in Southern

California, which is often

omitted from other ads, and

discusses the commitment

necessary to be a successful

orange grower. Oranges need

moisture to thrive, which

can only be supplied by

irrigation. Therefore, it is

important for farmers to

recognize this initial money

and energy. Although this

may seem like an

inconvenience, it is

actually a blessing in

disguise (according to

Edwards). One needs to be

entirely committed to caring

for the groves, so it is not

a job to be taken up

lightly. Orange groves can

only be successful “where

the greatest care had been

taken in cultivating,

picking, packing and

shipping” (Edwards, 68).

Although Edwards mentions

these necessary qualities,

he only mentions it in a

positive light. He doesn’t

describe the extent to which

one must be committed, such

as the labor, equipment,

wealth, and patience that

are required. He also fails

to admit that only a handful

of orange growers can be

successful; there was not an

extraordinarily large amount

of demand for oranges at

this time. When examining

articles, such as this one,

it becomes obvious that

magazines like Land of

Sunshine were attempting to

appeal to many different

demographics, and therefore

tended to omit many crucial

qualities of true California

living.

Edwards, Horace. “The Orange

in Southern California.”

Land of Sunshine, March

1894, 67-68.

Return to Top

|

|

Land of

Sunshine, article: “Some

Characteristics of the

Southern California

Climate” - Volume II, No.

1, Dec. 1894

- Danielle

Mantooth

"Mediterraneanism

and the Southern California

Climate"

One of the ways in which

Southern California was

marketed to residents of the

Eastern and Mid-Western

states was in terms of its

climate. Essential to this

promotion was the concept of

Mediterraneanism.

Mediterraneanism asserted

that Southern California

would grow into a society of

importance because of its

climate. Just as Rome and

Athens had become

influential centers, so

would Southern California,

simply because they shared

the same climatic

characteristics. Thus, the

particular weather of

Southern California became a

central focus of boosterism

for the state.

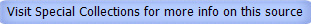

The magazine Land of

Sunshine made blatant and

copious references to the

sublime climate of

California. A photograph on

the cover of the December

1894 edition shows a winter

landscape in California.

Instead of snowdrifts,

rosebushes in bloom and

sunshine are featured. This

photo represents the broader

thesis of Southern

California boosterism.

Americans from other states

should travel to California

in search of a welcome

respite from the brutal

winters they have

experienced elsewhere, and

eventually make a permanent

move to this land of eternal

sun. Further discussion of

the merits of the

Mediterranean climate can be

found in an article written

for the magazine in 1894 by

Horace Edwards entitled

“Some characteristics of the

Southern California

Climate.” Edwards wrote that

the region “possesses a

distinctive climate,

considered by Southern

Californians a trifle

superior to any other on

earth” (42). Moreover, in

the area, “an average of 325

days in the year are

cloudless” (42). Remarks

such as these are meant to

entice the weary easterner

to Southern California by

pointing out the fact that

the weather is hardly ever

inclement, let alone snowy.

However, if anyone should

get the wrong impression,

Edwards claimed that “the

idea of Southern California

as an arid region is as

erroneous as the other idea

that we are flooded with

water during half the year

and dried up during the

other half” (43). This, of

course, is exactly the case,

but knowledge of this

situation would not have

convinced many to move to

the region. Edwards also

assures prospective

Californians from the

Mid-West that there is an

“absence of severe storms of

every description. Cyclones

and tornadoes…are here

entirely unknown” (43).

The entire purpose of Land

of Sunshine was to spread

the word about this new

Mediterranean paradise.

Southern California was

promoted as a sort of

“garden of eden” where

migrants could leave their

overcrowded, frigid cities

behind and find their own

place in the sun. When

Mediterraneanism is

considered, these jaded

transplants from the east

could be part of a “high

civilization” upon their

arrival. The underlying

principle being that since

Southern California shares

the same Mediterranean

climate with Greece and

Rome, that it too would grow

into an advanced society. In

reality, the climate of

Southern California may

leave much to be desired.

The fact that Edwards needed

to refute rumors about the

“aridity” of the region

suggests that the “garden”

aspect of this “garden of

eden” had been manufactured

and ardently cultivated.

Nonetheless, the climate of

Southern California

accounted for a large part

of boosterism in the late

nineteenth and early

twentieth century, as many

Americans travelled west in

search of paradise.

Return

to Top

|

|

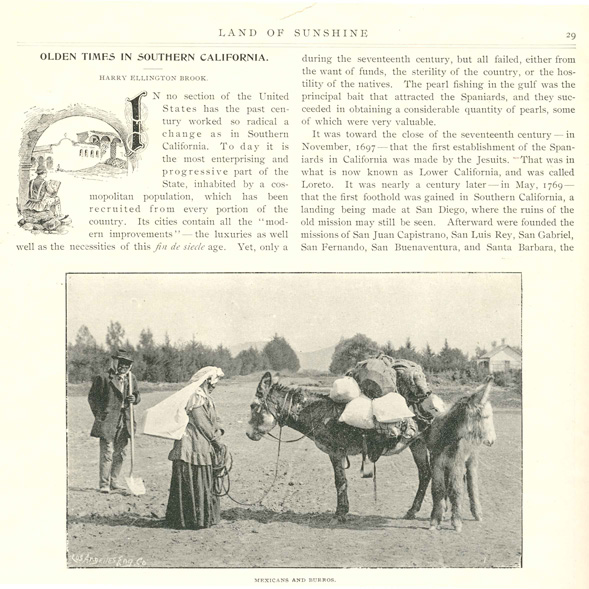

Land of

Sunshine, article:

"Olden

Times in Southern

California" - Volume I,

No. 3, August 1894

- Molly Nelson

Romanticization of

California’s Mission History

California boosters

harnessed the power of

California’s Spanish mission

history to contribute to

their image of California as

a land of beauty, plenty,

and most importantly,

leisure. According to the

1894 Land of Sunshine

article “Olden Times in

Southern California,” the

modern, “cosmopolitan,”

“enterprising and

progressive” Southern

California of 1894 still

retains the “easy-going

Spanish habit of putting

everything off until la

manana… a custom to which

the newly arrived gringo

readily accustomed himself”

(Lummis, 29). The California

boosters used a romanticized

vision of the agriculture,

real estate, and climate of

the Spanish missions and

their Native American

inhabitants to make

California as attractive as

possible to tourists and

potential residents.

Land of Sunshine takes care

to emphasize the calm,

idyllic aspects of Spanish

mission life, particularly

those elements which have

continued into the present.

Descriptions of agriculture

hide the reality of the

back-breaking, strictly

scheduled labor Indians

performed in the missions,

as described by Kent

Lightfoot in his book

Indians, Missionaries, and

Merchants (60). Instead, it

takes the form of “small

orchards and vineyards”

cultivated by the priests

and livestock “raised by the

aid of the converted

Indians” (Lummis, 29). This

quaint imagery does,

however, include essential

components of California

farming to which newcomers

to the region would be

attracted: orchards of nuts

and fruit and the production

of wine as well as meat and

dairy. The article’s

descriptions of Spanish

ownership and development of

land are also clearly aimed

towards potential buyers.

The lives of the rancheros,

the large landowners,

“constituted the height of

happiness,” with “A horse to

ride, plenty to eat, and

cigaritas to smoke… What

more could the heart of man

desire?” (Lummis, 31).

Similarly, the “one-story

adobe architecture” of the

period “formed a fitting

background to the easy-going

habits of the

pleasure-loving residents”

(Lummis, 29). This suggests

to potential real estate

buyers that they too could

experience the independent,

leisurely lifestyle of a

ranchero and suggests the

attitude they should have

towards purchasing and

developing land. The mild

Southern California climate

is also used as a selling

point for the past, when

life was “lived carelessly

and uneventfully, in the

land of sunshine, in those

early days” (Lummis, 31).

While the “accursed thirst

for gold” may have sped up

the pace of modern life, the

sun still shines on

California and this

effortless living is still

possible (Lummis, 31). By

selling California’s

enchanting Spanish history,

the boosters are also

selling the California of

the present.

This strongly romanticized

presentation of mission

history contributes to the

postcolonial Orientalist

discourse about the

subjugated Native American

population, “who found the

padres hard task-masters and

often longed for the earlier

days of unrestrained

liberty, before the white

man set foot on Alta

California” (Lummis, 29).

This article incorporates

romantic or positive

stigmatization as described

by Edward Said in his famous

work, Orientalism. This

attitude of positive

stigmatization is applied

not only to the domination

of the Spanish over the

Native Americans, but is

also used to discuss a

second level of domination –

that of the conquering

United States over the

Spanish colonizers

themselves. The descriptions

of the simple, “picturesque”

existence of the padres and

rancheros are also a form of

romantic stigmatization

(Lummis, 29). The California

boosters promote admiration

of the Spanish “other” for

their quaint, carefree

lifestyle in contrast to the

sophisticated “great

American commonwealth”

founded by the “adventurous

spirits” of western migrants

(Lummis, 31). This attitude

simultaneously celebrates

the perceived simplicity of

the past while establishing

modern-day Californian

civilization as superior.

Lightfoot, Kent G. Indians,

Missionaries, and Merchants:

The

Legacy of Colonial

Encounters on the California

Frontiers. Berkeley:

University of California

Press, 2006.

Lummis, Charles F. "Olden

Times in Southern

California." Land

of Sunshine, August 1894

Said, Edward W..

Orientalism. New York:

Vintage, 1979.

Return

to Top

|

|

Out West article:

“Hollywood, the

City of Homes” - Volume 21, No.

1, July 1904

- Stefanie Ramsay

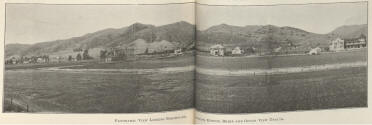

In

the early 20th Century,

California was marketed as a

perfect home for both

families and for those

looking for a new

cosmopolitan lifestyle. The

hope of advertisers was that

people who visited

California would make the

move permanent. One article

describing real estate in

Hollywood, “Hollywood, the

City of Homes”, exemplifies

the ways in homes and the

city were marketed to

prospective residents. While

the article may have been

convincing in its romantic

descriptions of Hollywood,

the truth of this city was

that it was not the center

of high culture yet and the

advertisements embellished

many facts of Hollywood. The

highly mythologized

presentation of real estate

in California gave emigrants

false hope of a new and

exciting lifestyle out west.

However, it was this myth

that led to the construction

of a glamorous Hollywood.

The homes in Hollywood in

1904, when this article was

published, are built in

various styles with the hope

that they would appeal to

wide range of people. In

fact, according to this

article, there is “not a

shabby home in town” (98).

There are homes built in

Mission style as well as

European style homes that

are built to show the

sophistication of the city.

Every home is described as

“rising from the Cahuenga

Valley…[with a] view of the

breakers at the Playa del

Ray” and located by the

Santa Monica Mountains (98).

Not only will a prospective

resident be intrigued by the

style of houses, but by the

beautiful location as well.

Above all, new residents

could feel “the velvety

softness of the air” and

smell that “the whole place

is filled with the perfume

of flowers” (97). Hollywood

was marketed to seem like a

vacation, but a permanent

one.

Thought it was marketed as

the perfect place to start a

new life, Hollywood was not

yet a bustling city of the

elite class, as is made

clear in the photographs

that accompany this article.

The photographed homes do

not appear to be unique but

seem fairly ordinary, with

no immaculate views of the

ocean or mountains, but

rather, set in surprisingly

desolate areas. This is a

startling contradiction in

marketing and highlights the

way in which romantic

language was utilized in

order to present a false

notion of Hollywood.

However, the myth of this

exciting city reflected the

hopes that Hollywood had for

its future and ultimately

produced the city that it is

today. People were attracted

to the city because of some

false advertising but then

built it to be the city that

they had dreamed about. This

can be seen in the promotion

of real estate. For example,

“homes have dancing parlors

and all have capacity for

quite elaborate functions”

(110), so that people could

entertain their guests in a

luxurious manner before the

city built venues to fulfill

that need. The reputation of

Hollywood as a city of

glamour started with the

false belief that it was

this way from the beginning,

but this myth was needed in

order to ultimately attain

that standing.

Lummis, Charles F.

“Hollywood, the City of

Homes.” Out West (1904):

97-111.

Return to Top

|

|

About

this Project / Acknowledgements

Occidental

College's "American Frontier"

Research Seminar was developed by

Dr. Jeremiah B.C. Axelrod, Adjunct

Assistant Professor of History.

The library project

is developed in collaboration with

the Special Collections

Department:

Dale Ann Stieber, Special

Collections Librarian

with student staff

Henry Boule and Claire Lem and

Laila Tootoonchi and Anahid

Yahjian.

Title Image:

Thomas Moran, "Nearing Camp,

Evening on the Upper Colorado

River, Wyoming, 1882," from

http://www.boltonmuseums.org.uk/collections/art/paintings_prints_and_drawings/oil/nearing_camp_moran

|

|

Page last edited on 03/12/2013.

Occidental

College Library Special

Collections & College Archives

© 2009 Occidental College

|

|

|

|

|