CHAPTER 9: Casablanca

[Summary: Casablanca is not only a great movie; it is also great art. Movies should be studied and appreciated as total works of art: characters, story, ideas, images, music. There are two parts to the chapter: (1) the history/making of Casablanca and (2) analysis/interpretation.]

"Casablanca, great art? Casablanca, ignored? With all due respect, sir, aren't you just using this as an excuse to talk about your favorite movie? . . ."

-- a friend of the author

Link back to Genius Ignored --Table of Contents

Link back to main page (Humanist Art Homepage)

Casablanca was considered to be a very good movie right from the time of its release in 1942. Since the 1960s it has generally been considered a great movie. But it has not been considered great art. I shall endeavor to convince you, here and in the succeeding chapter, that not only is Casablanca important as art, but that movies, in general, are the most important art form of the 20th century.

There is a category of movies which are considered to be art; they are "art films". The very existence of this term tells us that other films are considered to not be art -- except, perhaps, "popular art". We would do well in this regard to remember Shakespeare. His plays, containing, in addition to their lofty thoughts, spectacular and sentimental elements, were extremely popular. Theater (like cinema in our own day) was a relatively new form. The intellectual elite enjoyed the plays but didn't consider them to be in the same class as the really great art of Virgil and Horace. The texts of the plays barely escaped oblivion. (An interesting parallel to the way in which originals of early movies have been allowed to deteriorate.)

It is a mistake to assume that because art is popular it can not be great. Truly great art resonates on a number of levels.

Part 1: The History/Making of the Casablanca

Most of the art discussed in this book was the work of a single person and, though movies, by their nature, require collaboration, most great films have a single, powerful director with a clear vision shaping them; Casablanca did not. The 1940s Warner Bros. studio which made the picture was geared toward cost-efficient, profitable production. Such production was achieved through carefully-defined responsibility: the music director created the music; the lighting director lit the set; writers wrote. One of the producer's jobs was to prevent the general director from tampering excessively with these other people's creations. As we shall see, Hal Wallis, the producer of Casablanca, did much more than this, playing a very active and important role personally.

It was Michael Curtiz, the director, and Hal Wallis, the producer, good friends, long-time associates, working together, who guided Casablanca.

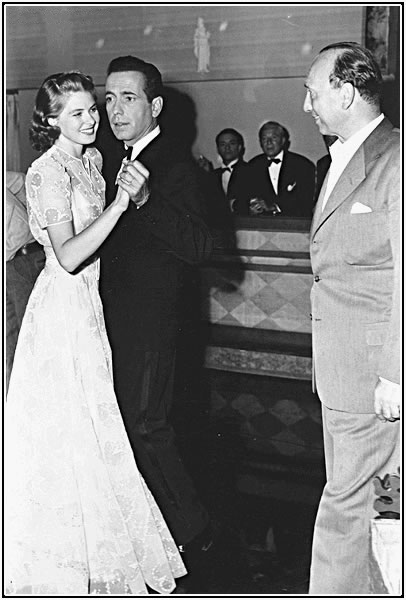

[Michael Curtiz at right, directing Bogart and Bergman]

In 1931 a Cornell University senior, Murray Burnett, played "As Time Goes By", a song from the then-current Broadway show, Everybody's Welcome, so often that his fraternity brothers got sick of it. The song disappeared from the radio and from the record stores, but lingered on in Burnett's memory.

In 1938 Burnett, a Jew, now married, traveled with his wife to German-occupied Vienna to help relatives smuggle possessions out of the country. They were shocked by the hatred shown toward Jews and terrified by the direction things seemed to be going.

In 1940 Burnett, collaborating with a friend, Joan Alison, used his Vienna experience as the basis for a play, Everybody Comes to Rick's. The protagonist is a cynical, unhappily married American expatriate who owns a nightclub in Casablanca. His former lover Lois appears at the club with the Resistance leader, Victor Laszlo. She asks Sam, the black piano player, to play "As Time Goes By". Lois' passion for Rick is rekindled. She decides to stay with him in Casablanca. In Victor's presence Rick insists that she leave. Victor, despite having been humiliated by her, takes her with him.

During 1941 the completed play was circulated to various Hollywood studios. A producer at M-G-M wanted to buy it for $5000, but his boss objected. Eventually it came to the attention of Irene Lee, head of Warner Bros. story department. The bombing of Pearl Harbor and the United States' entrance into the war in early December had made the play more topical and valuable. On December 27, 1941, with Hal Wallis' approval, she purchased Everybody Comes to Rick's for $20,000.

Harold Brent Wallis had been born in Chicago, Illinois, on September 14, 1899, of Jewish immigrant parents. Starting in the publicity department at Warner Bros. in 1923, he had worked his way up to producer by 1928 and in 1933 had taken over as chief producer when Darryl Zanuck left to form 20th Century. He was business-like, quiet, prolific, and underrated. During his tenure, Warner Bros. turned out consistently above-average pictures.

Despite the nonsense which Warner Bros.' publicity department circulated in January, 1942, about Ronald Reagan starring in the picture, Wallis had Bogart in mind from the start. In December, before the play had even been purchased, Wallis had received the suggestion from script-reader Stephen Karnot: "A box-office nautral -- for Bogart, Cagney, or Raft in out-of-the-usual roles." And from fellow producer Jerry Wald: "This story should make a good vehicle for either Raft or Bogart." On February 14 Hal Wallis told casting director Steve Trilling that Bogart would star in Casablanca.

Humphrey DeForest Bogart was born in New York City on January 23, 1899. His father was a doctor and his mother, a successful illustrator and commercial artist. In a 1949 magazine article Bogart would claim that he never really loved his mother, that he admired her but that 'she was totally incapable of showing affection,' even to her three children." [quoted in Harmetz, p. 84] He was educated at Trinity School and Phillips Andover Academy but instead of going to college he enlisted in the Navy, serving for the duration of World War I. In the 1920s he worked as, first, a stage manager and then as an actor and then decided to try his hand at movies. His performances in a dozen films in the early '30s were undistinguished. But in 1935-6 he played the brooding killer Duke Mantee in both the stage and movie versions of The Petrified Forest. After that, more and more of his roles were variations on this cynical, tough-guy persona. It was not until High Sierra in 1940 and The Maltese Falcon in 1941 that Bogart got starring roles. He brought to these roles the same exterior toughness, but had the chance to exhibit deeper, more complex emotions on the inside.

In February, 1942, Wallis discussed the play with two of the studio's top writers, the Epstein twins, Julius and Phil. They were excited. "We thought the play would make a wonderful movie. It had a lot of juice to it. And we loved Bogart's character." [quoted in Harmetz, p. 43] The Epsteins were known especially for their "sparkling" dialog. As we shall see, other writers would work on Casablanca, but the Epsteins did most of the work. They can be credited with:

* the transformation of Captain Renault from a minor, rather unpleasant, womanizer into a superbly witty, sophisticated friend of Rick;

* the transformation of Rick from a self-pitying, adulterous lawyer into a tough, cynical man with unsuspected resources of tenderness, consideration, and strength;

* the marvelous banter between Rick and Captain Renault;

* all the scenes which take place before Rick is introduced;

* the humor.

When the Epsteins gave Wallis the first third of the movie in April, Wallis immediately turned around and gave it to another writer, Howard Koch, for his suggestions, while having the Epsteins continue to work on Part II. Koch was younger, more political. (Later, during the McCarthy era, he would be blacklisted.) He gave Wallis 19 pages of "Suggestions for a Revised Story".

"There is also a danger that Rick's sacrifice in the end will seem theatrical and phony unless, early in the story, we suggest the side of his nature that makes his final decision in character. It would be interesting to have Renault penetrate the mystery in the first scene with Rick when he guesses that the cynical American is underneath, a sentimentalist. Rick laughs at the idea, then Renault produces his record--'ran guns to Ethiopia,' 'fought for the Loyalists in the Spanish War.' Rick says he got well paid on both occasions. Renault replies that the winning side would have paid him better. Strange that he always happens to be on the side of the under-dog. Rick dismisses the implication, but through-out the picture we see evidence of his humanity, which he does his best to cover up." [quoted in Harmetz, pp. 56-7]

Koch makes the man Rick bars from his gambling room--who was an English cad in the play--into a representative of the Deutschbank. [Harmetz, p. 57]

. . . Koch solved the unworkable subplot by having Rick allow the young Bulgarian couple to win at roulette.

In their script of April 2, the Epsteins had incorporated a real-life incident. Phil's wife, Lilian, had played 25-cent roulette in Palm Springs and lost. "She was moaning and complaining about losing," says Julie. "Finally the croupier told her put her chips on 22. She won, and he told her to get out and never come back." The Epsteins created a refugee who had been saving for three years enough money to leave Casablanca and was now gambling away his stake. Rick told him to put his money on 24 [sic], and he won.

. . . Koch zeroed in on this scene as a way of showing Rick's humanity:

"Why not make this a much bigger situation--for instance, it might be the way he rescues Annina and her husband from Renault? The Prefect has named a price for the visa too high for the couple to pay. In his most gracious manner, he suggests to Annina that she can pay in another way. . . . Annina comes for advice to Rick, who enables Jan to win at roulette, thus defeating the intention of his friend Renault. The Prefect, when he learns, should not resent this action of Rick's, but accept it as a sporting loss--and also as proof of his argument that Rick is a sentimentalist." [Harmetz, p. 59]

Koch rewrote the Epsteins to give the movie more weight and significance, and the Epsteins then rewrote Koch to erase his most ponderous symbols and to lighten his earnestness. [Harmetz, p. 56]

Wallis' first choice for director was William Wyler. When that didn't work out he turned (sometime in mid-February) to his friend Mike Curtiz. Mihaly Kertesz was born in Hungary on December 24, 1888. By the time he came to Los Angeles and Warner Bros. from Austria in June, 1926, he had already made sixty-two silent movies. The studio person assigned the task of meeting him at the train station was publicity man Hal Wallis. "During the decade between 1930 and 1940, he [Curtiz] directed forty-five talking pictures. They may have been a goulash of melodramas, horror films, swashbucklers, westerns and gangster movies . . . but his movies had three things in common. They were brought in on time, they rarely went over budget, and they almost always made money. . . ." [Harmetz, p. 63]

Mike didn't have much time to think about Casablanca that spring; he was busy finishing Yankee Doodle Dandy (--not a bad picture in its own right).

In Everybody Comes to Rick's the Ilsa character is "an American tramp named Lois Meredith, whose affair with Rick ended when she casually cheated on him with another man and whose renewed affair with Rick in Casablanca emasculates her current lover, Laszlo." [Harmetz, p. 47] Casey Robinson, Wallis' favorite -- and Warner Bros.' highest paid -- screenwriter had the idea that the heroine should be European. Michele Morgan, an actress of French descent, and Ingrid Bergman quickly became the two main contenders. They were about the same age, each had made several successful movies, and they seemed about equally promising. But the studio would have had to have paid Morgan $55,000, while they could get Bergman for $25,000. The deal with David O. Selznick/Paramount Studios to lend Ingrid Bergman to Warner Bros. for eight weeks was finalized in late April.

Ingrid Bergman was born in Sweden, on August 29, 1915. Her mother died when she was three; her father, when she was twelve. After attending Stockholm's Royal Dramatic Theater School for a year, she had been offered a film contract. David Selznick had seen her in the 1936 Swedish film Intermezzo and, in 1939, had brought her to America to star in his English-language version. She made several movies in 1940-1 but things had gone dry by 1942. Her husband, Petter Lindstrom, had been a dentist in Sweden and they were now living in Rochester, New York, where he was studying to be a neurosurgeon. She was not happy. She wrote to her friend and dialogue coach Ruth Roberts in January 1942:

". . . Having a home, husband, and child ought to be enough for any woman's life. I mean, that's what we are meant for, isn't it? But still I think every day is a lost day. As if only half of me is alive. The other half is pressed down in a bag and suffocated." [quoted in Harmetz, p. 90]

On April 22, after learning she had gotten the role in Casablanca, she again wrote Roberts:

I was warm and cold at the same time. Then I got such chills I thought I must go to bed and of course a terrific headache into the bargain. . . . I tried to get drunk for celebration at dinner, but I could not. I tried to cry. I tried to laugh, but I could do nothing. I went to bed three times and went down again because Petter couldn't sleep either with me kicking around in bed. But now it is morning and I am calmed down. The picture is called Casablanca and I really don't know what it's all about. [quoted in Harmetz, p. 95]

If Humphrey Bogart as Rick and Ingrid Bergman as Ilsa were essential to the success of Casablanca, other casting decisions were important too.

Though the Epsteins' Captain Renault is a brilliantly-written character, it's hard to imagine anyone else delivering these lines as well as Claude Rains. Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet are superb in their respective roles as Ugarte and Senor Ferrari.

Most of the other characters in the film are also well-realized. Warner Bros. had a wealth of actors available to them. In particular, there was a surplus of European refugees well-suited to playing the European refugees (and German officials) in Casablanca. Actors who had been stars in Europe gratefully accepted bit parts in America.

As the late-May date for the start of production neared, most of the script was in pretty good shape. But Wallis felt that there were still problems with the Ilsa character and the ending. He called in Casey Robinson. On May 20, Robinson sent Wallis seven pages of notes. They began: "Again, as before, my impression about CASABLANCA is that the melodrama is well done, the humor excellent, but the love story deficient." [quoted in Harmetz, p. 173] A specific example:

In place of this scene, I would play the scene where Ilsa tries to find out from Sam where Rick is. Think a minute of the facts of the love story and you will see why this scene is necessary. The girl has just one thing in mind, that she must get to Rick and tell him why she didn't catch the train in Paris. Loving him as she does, and suspecting what he thinks about her, she must clear this up. Now, she need not disclose this motive to Sam, in fact, shouldn't but the audience will realize it later. In the meantime, this business serves as a very good buildup for the love story and will pique the audience's interest and make the first meeting between Ilsa and Rick tremendously effective. [quoted in Harmetz, p. 176]

Production of Casablanca commenced on May 25, 1942. The cameraman was Arthur Edeson. One of the fifteen original members of the American Society of Cinematographers, he had been operating movie cameras since 1913. He expressed his views on his craft as follows:

The principal factors are always the story and the actors. The picture Maltese Falcon called for strong, modernistic, eye-arresting camerawork. Other pictures require that the camerawork be as inconspicuous as possible to heighten the illusion of realism and perhaps keep it from overpowering a weak story. The best thing is to strive to always keep things as simple as possible photographically speaking. And if lighting and composition are kept simple and the accent is placed on the story and actors rather than on the camera, we can't go very far wrong. [quoted in Harmetz, p. 134]

After seeing the first scenes from Rick's Cafe, "Wallis asked for more contrast and sent Edeson to examine tests of Michele Morgan and Jean-Pierre Aumont, which had the look he wanted. 'I am anxious to get real blacks and whites, with the walls and the backgrounds in shadow, and dim, sketchy lighting.'" [Harmetz, p. 136]

The first couple days on the set were pretty rough. Curtiz was not exactly the easiest guy in the world to work for and there were other conflicts. But as Francis Scheid, the soundman, later observed, "All the pictures I worked on where everybody was lovey dovey ended up lousy." [Harmetz, p. 136]

Rewriting continued. "Eight months later, when Jack Warner wanted to complain about out-of-control scripts, he had Steve Trilling send a memo to all the studio's producers. Casablanca was his major example of scripts so out of control that the writers had to rewrite while the movie was shooting and, thus, were not available for any other work." [Harmetz, p. 172]

Generally Curtiz respected the wishes of Wallis and the writers but, of course, they weren't actually on the set. It was Curtiz who had Ilsa pound the table with her fist, knocking over the wine glass, in the climactic scene between her and Rick in Paris. Wallis was quite upset about other changes:

The transition from driving down the Champs-Elysees to the country road means nothing because you left out the dialogue. . . . For the balance of the picture I will greatly appreciate it if you will call me on the telephone when you drop dialogue out of a scene, or make changes, as it will be far simpler, and considerably less expensive for us to discuss these things before you do them than to go back and retake scenes later. [quoted in Harmetz, p. 187]

As we can see, however, these scenes were not re-shot and remained without dialogue.

The line "Here's good luck to you" was changed during shooting to "Here's looking at you, kid" -- apparently at the suggestion of Bogart himself.

Curtiz was certainly responsible for the breathless pace of the movie. That was his trademark. He lingers over conversations and activities only when they're essential. Even after repeated viewings, Casablanca is absolutely riveting.

Despite myths to the contrary, there was never really any question that Casablanca would end with Ilsa accompanying Victor to Lisbon. The question was how to make it work.

"In Everybody Comes to Rick's, as in Casablanca, Rick tricks Renault into calling off his watchdogs, then pulls a gun on him in order to allow Laszlo and Lois to escape . . . Just as the Lisbon plane is taking off, Strasser rushes into the cafe. Rick holds the gun on Strasser as long as necessary, then throws it contempuously on the table. As he walks out, under arrest, Renault . . . asks, 'Why did you do it, Rick?' Rick reminds the policeman that he won his bet that Laszlo would escape. 'For the folding money, Luis. You owe me five thousand francs.'" [Harmetz, p. 230]

With America now at war, an ending in which the Gestapo have any sort of triumph at all was out of the question. The confrontation was moved to the airport; Strasser draws his gun on Rick and is shot; Renault, hesitating only an instant, issues the command to "round up the usual suspects".

There was also, however, the equally large problem of making Ilsa's departure with Laszlo believable.

"In the play a thoroughly disagreeable Lois insisted on staying with Rick. 'That, my dear, is entirely up to you,' a humiliated Laszlo answered. 'Get her out of here, Victor, for God's sake,' said Rick. To add to the unpalatability, Laszlo was grateful to Rick for giving him a woman who didn't want to be with him." [Harmetz, p. 230]

In a July 6 memo to Curtiz, Wallis expresses his frustration:

It was practically impossible to write a convincing scene between the two people in which Rick could sell Ilsa on the idea of leaving without him. No arguments that Rick could put up would be sufficient to sway her from her decision to remain, . . . [quoted in Harmetz, p. 234]

But by moving this scene too to the airport and having Laszlo present, Ilsa is taken by surprise and convincingly overwhelmed.

July 22 was the last day of regular shooting. The movie was turned over to veteran composer Max Steiner to do the music. He "hated 'As Time Goes By' and persuaded Wallis to allow him to replace it with a love song of his own. But, lucky accident, Ingrid Bergman had already had her hair cut short for her part in For Whom the Bell Tolls and could not reshoot the necessary scenes." [Harmetz, p. 7] "Since he was stuck with 'As Time Goes By,' Steiner did more than give in gracefully. He proceeded to make 'As Time Goes By' the centerpiece of the score. The song was not only Rick and Ilsa's love theme but Steiner's main connecting device. The song linked Rick and Ilsa, present and past, the source music to the underscoring, and the audience to the characters in the movie." [Harmetz, p. 255]

Wallis continued to tinker. In mid-August he added the early scene with the police official announcing (over police radio) that two German couriers had been murdered. And he had Bogart record an additional line for the ending: "Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship."

When one looks at the individual elements of the movie -- the script, the acting, the photography, the direction, the music, the editing -- it's hard to find anything (except, perhaps, the performances of Bogart and Bergman) that one could call extraordinary, and yet, working together in a beautiful balance, never calling attention to themselves, a Bach concerto of sorts, they result in a truly extraordinary whole.

The film opened in one New York theater on Thanksgiving Day, 1942, but wasn't generally released until January, 1943. It did well at the box office, seventh in total receipts for 1943. "A poll of 439 critics and commentators taken by Film Daily called Casablanca the fifth-best movie of the year -- behind Random Harvest, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Yankee Doodle Dandy, and This Is the Army." [Harmetz, pp. 12-3] Though it was ignored in the National Board of Review's and the New York Film Critics' awards, it won the Motion Picture Academy's awards for Best Screenplay, Best Director, and Best Picture. After that it faded from view.

Lauren Bacall describes (her husband) Humphrey Bogart as being "very pleased the movie was successful, but, mind you, it wasn't the success in his lifetime that it is now [1992]." [Harmetz, p. 232] Bogart died in January, 1957. In April of that same year the Brattle Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts, started playing some of his old movies; Casablanca, first and foremost. It continued to grow in popularity during the 1960s and 1970s and has maintained its status as an audience favorite since then. But it's not considered art. It lacks the technical/visual virtuosity which would make it of interest to film students. And, of course, movies are simply not considered suitable subjects for study of their content, in the way that plays and novels are -- let alone studied and appreciated as they should be: as total works of art: characters, story, ideas, images, music. We're too compartmentalized, can't handle art (or, for that matter, a book about art) which crosses all these boundaries. . . .

Part 2: Analysis/Interpretation

Casablanca starts as a newsreel: a slowly-turning globe, a documentary-style narrator. The events which follow are fictitious, but they take place in a real world where things like this really do happen. . . .

War-time Casablanca is a polyglot city of Moors, French, German officials, and refugees from all over Europe, the latter trying to get to Lisbon and freedom. Tensions are high. We see police shoot a man who refuses to obey their order to stop. A second later, in a different place, a dark European warns an English couple of the "scum of Europe", "vultures", -- as he deftly lifts the husband's wallet. Their conversation takes place at a normal, leisurely pace but the instant it's done we are interrupted by the sound of a plane. Faces turn skyward: all nationalities and ages; not the faces of actors at all; humble, ordinary faces. We sense that it is not just this small crowd on a street in Casablanca which is looking at the plane, yearning for freedom, but humanity as a whole. . . .

A bit overwrought? Perhaps. But consider the context (things its makers didn't feel it was necessary or politic to mention in that spring and summer of 1942):

* German forces, after a brief setback the previous winter, were once again advancing in Russia; U-boats sank 900 Allied ships that spring and threatened to cut off Britain; after Russia was conquered the Germans would be able to turn their full attention to England.

* Rommel's Afrika Korps had driven deep into Egypt; Alexandria, Cairo, and the Suez Canal were threatened.

* Following Pearl Harbor, the Japanese had conquered Singapore, Burma, and the Philippines;

In retrospect we know that this was the zenith of Axis power -- but for refugees on the streets of Casablanca, for writers and actors in the Warner Bros.' Hollywood studio, that spring and summer of 1942, no such thing was clear at all.

Cut to the airport where the plane lands. A German officer, Major Strasser, disembarks. He is greeted by Captain Louis Renault, Casablanca's Vichy French Prefect of Police. We take Louis right off the bat for the witty, sophisticated, irrepressibly devilish character that he is, his police cap held at a jaunty angle over his nicely-styled hair.

Then it's evening. We're at Rick's Cafe Americain. Everybody comes to Rick's.

. . . Rick's is an expensive and chic nightclub which definitely possesses an air of sophistication and intrigue. . . . There are Europeans in their dinner jackets, their women beautifully begowned and bejeweled. There are Moroccans in silk robes. Turks wearing fezzes. Levantines. Naval officers. Members of the Foreign Legion, distinguished by their kepis.[Koch, p. 35]

The dark, busy cafe is filled with smoke, and with people plotting their escape.

. . . In the foreground at the table we see a drink and a man's hand. The overseer places a check on the table. The man's hand picks up the check and writes on it, in pencil: "Okay-Rick." The overseer takes the check. The camera pulls back to reveal Rick, sitting at a table alone playing solitary chess. There is no expression on his face. . . . [Koch, p. 40]

We recognize him as the tough-guy Bogart has played many times before. He says nothing. Just nods his approval or disapproval of particular people seeking entrance to the gambling room. When a German official tries to force his way in, Rick refuses to be intimidated: "Your cash is good at the bar."

A man whose name we later learn is Ugarte comes to sit at Rick's table. Ugarte is wonderfully slimy, fawning, nervous. His question to Rick, "You despise me, don't you?" has no hint of malice or sarcasm in it. It's as though he is fully aware how contemptible he is and assumes that honest people will see him as such. But rather than making us despise him his question intrigues and saddens us; surely a man with this much candor is no ordinary man. And then Ugarte asks Rick to safeguard the letters of transit: "I have many friends in Casablanca, but somehow, just because you despise me you're the only one I trust. . . ." This doesn't make sense, but what does come across clearly is the fact that Rick is extremely trustworthy. When they were both sitting down, they seemed pretty much on a par, now as Ugarte gets up to leave, Rick likewise rises and confronts Ugarte with this serious matter of the murder of the couriers and we get a sense of Rick's imposing physical presence. <In multimedia version, when we can have full-motion video interspersed with the text, please insert at this point Rick's entire conversation with Ugarte.>

Rick goes out into the main room where Sam is playing "Knock on Wood". He hides the letters in the piano. Another man with an imposing physical presence enters the cafe: Signor Ferrari. Two seconds after Sam finishes, Ferrari is at Rick's side. (There is absolutely no wasted time in this movie.) He wants to buy Rick's cafe or, failing that, his piano player. Sam's refusal to accept Ferrari's offer of a 100% increase in salary impresses us. And we feel that a man who can inspire this kind of loyalty must have some very admirable qualities of his own.

The ensuing business with the beautiful, passionate, drunk Yvonne likewise sheds light on Rick: for such an attractive woman to be so infatuated with him, he must be pretty special. This leads into a brilliant exchange between Rick and Captain Renault: <Renault:> "How extravagant you are throwing away women like that. Someday they may be scarce." (This last sentence was originally "Someday they might be rationed." but government censors objected and the line was changed.)

<Renault:> "I have often speculated on why you don't return to America. Did you abscond with the church funds? Did you run off with a senator's wife? I like to think you killed a man. It's the romantic in me."

<Rick:> still looking in the direction of the airport. "It was a combination of all three."

<Renault:> "And what in heaven's name brought you to Casablanca?"

<Rick:> "My health. I came to Casablanca for the waters."

<Renault:> "Waters? What waters? We're in the desert."

<Rick:> "I was misinformed."

<Please include the entire outside conversation between Rick and Renault in multimedia version.>

When Renault tells Rick that they will be arresting Ugarte and advises against trying to warn him, Rick replies, "I stick my neck out for nobody." When Renault later informs Rick, "There is a man who's arrived in Casablanca on his way to America. He will offer a fortune to anyone who will furnish him with an exit visa." Rick's response is a flat, uninterested "Yeah? What's his name?" (No one can do this better than Bogart.) When Renault replies, "Victor Laszlo" we see a strange expression of discomfort pass across Rick's face -- as though he instinctively knows that the presence of this great man in Casablanca will somehow affect him too.

A Bogart who inspires trust, loyalty, and passion is perfectly consistent with the tough-guy persona, but this Rick Blaine who can be so impressed by Victor Laszlo doesn't seem to quite fit. . . . More great dialogue at this point:

<Renault:> ". . . No matter how clever he is, he still needs an exit visa, or should I say, two."

<Rick:> "Why two?"

<Renault:> "He is traveling with a lady."

<Rick:> "He'll take one."

<Renault:> "I think not. I have seen the lady. . . ."

When the police arrive to arrest Ugarte, we see the latter squirming, terrified, an animal caught in a trap. He runs to Rick. His pleas for help are desperate, visceral. <Please include clip of entire bravura performance by Lorre in multimedia version.> We do not fault Rick for failing to help Ugarte. It would have been foolish. He acts in the tough, rational manner we expect of him.

Captain Renault sits down at Major Strasser's table and then asks Rick to join them. Renault delivers one of his patented double-entendres: "We are very honored tonight, Rick. Major Strasser is one of the reasons the Third Reich enjoys the reputation it has today." After Major Strasser probes Rick's background and allegiances, he confronts Rick with a "complete dossier" they have on him. After glancing at it, Rick responds with classic-Bogart boldness/impertinence: "Are my eyes really brown?"

and then leaves the table: "You'll excuse me, gentlemen. Your business is politics. Mine is running a saloon."

The camera shifts to the door of the cafe as Victor Laszlo and his companion, Ilsa Lund, enter. His off-white suit and her elegant but simple white dress are highlighted against the black of the headwaiter's uniform. There's an air of authority in his statement "I reserved a table. Victor Laszlo." And in the way he walks across the room. We are inclined to agree with Captain Renault: Laszlo's companion is very beautiful. She keeps pace with him with surprising ease and slips into her seat gracefully. She's nervous -- apparently because of the Nazis, but, as we learn later, for another reason too . . . It is she who spots the approaching Captain Renault and issues a quiet, curt "Victor!" to cut short his conversation with Berger, the Norwegian. Laszlo towers over Renault as he rises to greet him. When Renault says to Ilsa, "I was informed that you were the most beautiful woman to ever visit Casablanca. That was a gross understatement." She smiles graciously. No false modesty, no coy protests, just a simple "You are very kind."

When she asks Captain Renault about Sam, the piano player, Renault responds "He came from Paris with Rick."

<Ilsa:> "Rick? Who's he?"

<Renault:> smiling "Mademoiselle, you are in Rick's and Rick is, er . . ."

<Ilsa:> "Is what?"

<Renault:> "Well, Mademoiselle, he's the kind of man that, well, if I were a woman and I . . . tapping his chest . . . were not around, I should be in love with Rick. But what a fool I am talking to a beautiful woman about another man."

With this last sentence a faint glimmer appears on her face and quickly blossoms into a beautiful, full-fledged smile, directed not at Captain Renault but at (the man we later learn is) her husband -- as though he, too, should take pleasure in the Captain's flattery. (We shouldn't forget how much Ilsa is sacrificing in this 1940s society by keeping her marriage to Victor a secret; a "companion" was viewed and treated very differently than a wife. . . .)

When Major Strasser comes to their table, Victor refuses to stand and shake his hand. There is a strong, mutual, hostility. When Strasser leaves, Victor says to Ilsa, "This time they really mean to stop me." Ilsa responds, "Victor, I'm afraid for you." She is looking at him intently, not averting her eyes for a second; dead-serious. Victor leaves to talk with Berger at the bar. Ilsa asks the waiter to have Sam come over. Sam comes, bringing the piano. They know each other. When Ilsa inquires about Rick, Sam tries to divert her (". . . he's got a girl up at the Blue Parrot. He goes up there all the time.") Ilsa's expressions are exquisite: bemusement; hurt; radiant joy at the memory of these songs. Turning away, reaching for her wine glass, she responds quietly, "You used to be a much better liar, Sam." Brushing aside his ensuing plea ("Leave him alone, Miss Ilsa. You're bad luck to him."), as though under a spell, she orders him "Play it, Sam. Play, 'As Time Goes By'." When Sam protests that he can't remember the tune, she says "I'll hum it for you." -- and does. Throughout this conversation her voice and face are filled with a rapturous beauty.

{ . . . And thereupon

That beautiful, mild woman for whose sake

There's many a one shall find out all heartache

On finding that her voice is sweet and low

Replied . . . (W. B. Yeats, "Adam's Curse")}

Sam starts to play "As Time Goes By". Rick hears it as he comes out of the gambling room and is very disturbed, "Sam, I thought I told you never to play . . ." There are powerful emotions at work for Rick Blaine to be so upset by this song, this woman. . . .

It is a brilliant stroke to have Ilsa and Rick interrupted at this point by Renault and Laszlo: our suspense about their relationship is prolonged and we get to see the interesting puzzlement of the other characters. Rick shows integrity and generosity by not letting Victor's relation to Ilsa get in the way of his feelings about him:

<Laszlo:> "This is a very interesting cafe. I congratulate you."

<Rick:> "And I congratulate you."

<Laszlo:> "What for?"

<Rick:> "Your work."

<Laszlo:> "Thank you. I try."

<Rick:> "We all try. You succeed."

Rick and Ilsa's initial probing takes place under the watchful eye of Captain Renault: "I can't get over you two. She was asking about you earlier, Rick, in a way that made me extremely jealous."

Rick is seething inside, looking darts at this woman, never taking his eyes off her for an instant. She, in contrast, is flooded with memories of Rick and Paris, unable to suppress a ravishing, radiant smile -- but at the same time puzzled, fearful of what he must think of her.

Afterwards, outside the cafe, alone with her husband, she assumes an air of nonchalance:

<Laszlo:> "A very puzzling fellow, this Rick. What sort is he?"

Ilsa doesn't look at him.

<Ilsa:> "Oh, I really can't say, though I saw him quite often in Paris."

<Please include entire scene from Ilsa starting to speak with Sam to Ilsa and Victor outside the cafe in multimedia version.>

Why does Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca seem infinitely more lovely than the fashion models society holds up as paragons of beauty? . . . I will go out on a limb here: just as we, centuries later, marvel at the beauty of Michaelangelo's David, the Venus de Milo, and the funerary stele of Hegeso, so people hundreds of years from now will marvel at the beauty of Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca. Kind Reader! I beg, in advance, your indulgence of a brief digression on the nature of beauty:

I SAY THERE IS NO PHYSICAL BEAUTY

I say there is no physical beauty.

This skin, this flesh, this bone

are but the clay of which we make our beauty,

the instrument on which we play our beauty.

Witness the failure of funeral directors to please true aesthetes:

the dead Ingrid Bergman lacks the beauty of a living bag lady.

Tennis masters

given K-Mart rackets

win gracefully,

while the high-school violinist

playing a Stradivarius

fails to delight us.

Thus noses, lips, breasts have no beauty in themselves.

Perfect features are easily distorted by

anger, sloth, irritability, or conceit.

But in a rare few

energy, grace, composure, and sensitivity

are blended in such a quantity

that they overflow

and color with an exquisite beauty every pore of the body,

fill with a subtle music every gesture, every word.

I say there is no physical beauty.

This skin, this flesh, this bone

are but the clay of which we make our beauty,

the instrument on which we play our beauty.

<Link to some of author's other poems >

Intelligence, passion, the unguarded "sorrows of her changing face . . ." Some people would say that Ilsa Lund lacks warmth, the animal energy of a Sophia Loren or a Susannah York. I don't disagree, but would argue that there is to the greatest beauty a certain reserve, a certain holding-back; a dignity; a refusal to give one's self up entirely to the transient and the corporeal; a sensitivity to the basso continuo of mortality, to whose accompaniment we play our lives. . . .

Later that same night. The streets are deserted. Rick and Sam are alone in the cafe. Rick has been drinking. He's waiting for Ilsa, convinced she'll be coming back. (Always seemed like kind of a long-shot to me: the curfew, a woman alone, guys like Ugarte running around . . . ) "As Time Goes By" takes us back to pre-Occupation Paris. Rick and Ilsa have met and fallen in love. (As we learn later she was, even then, married to Victor Laszlo but thought he was dead.) Though it's not exactly a strong suit for either of them, Bogart and Bergman do well as a playful, newly-fallen-in-love couple. Political events intrude: tanks, planes, Nazis on the outskirts. Rick's anti-Fascist record makes staying in Paris risky.

Though we don't find out until later, Ilsa learns at this moment that Victor is still alive.

There is only a handful of actresses who could make lines like "With the whole world crumbling, we pick this time to fall in love." convincing. But a great actress can find the underlying truth -- yes, it would seem like the world was crumbling; yes, people do fall in love. . . .

<Ilsa:> "Was that cannon fire, or is it my heart pounding?"

<Rick:> "Ah, that's the new German 77. And judging by the sound, only about thirty-five miles away."

Only Bergman and Bogart could have pulled this one off.

As Ilsa speaks what turn out to be her parting words for Rick, we feel her deep passion: "Oh, it's a crazy world. Anything can happen. If you shouldn't get away, I mean, if, if something should keep us apart, wherever they put you and wherever I'll be, I want you to know that I . . ." The fist knocking over the wine glass could have been trite, but, because there's real passion here, it's brilliant; a physical expression of her anger (at fate) -- and of her strength.

Ilsa does return to the cafe.

<Ilsa:> "Please don't. Don't, Rick! I can understand how you feel."

<Rick:> "Huh! You understand how I feel. How long was it we had, honey?"

<Ilsa:> "I didn't count the days."

<Rick:> "Well, I did. Every one of them. Mostly I remember the last one. A wow finish. A guy standing on a station platform in the rain with a comical look on his face, because his insides had been kicked out."

Ilsa, alienated by Rick's drunken rudeness, leaves.

The next morning Victor and Ilsa visit Major Strasser at Captain Renault's office. Strasser summarizes the situation succinctly: "You are an escaped prisoner of the Reich. So far you have been fortunate enough in eluding us. You have reached Casablanca. It is my duty to see that you stay in Casablanca." His attempt to intimidate Victor into giving the names of European resistance leaders seems preposterous -- until he reveals that Ugarte is dead, apparently executed.

Rick goes to visit Signor Ferrari at the Blue Parrot. Their conversation is a masterpiece of blunt cynicism:

<Ferrari:> chuckling "Carrying charges, my boy, carrying charges. Here, sit down. There's something I want to talk over with you, anyhow." hailing a waiter "The bourbon." to Rick, sighing deeply "The news about Ugarte upset me very much."

<Rick:> "You're a fat hypocrite. You don't feel any sorrier for Ugarte than I do."

<Ferrari:> eyes Rick closely "Of course not. What upsets me is the fact that Ugarte is dead and no one knows where those letters of transit are."

Rick leaves <please include entire scene between Rick and Ferrari in multimedia version>; Victor and Ilsa come in. When Victor says: "Signor Ferrari thinks it might just be possible to get an exit visa for you." Ilsa's response, "You mean for me to go on alone?" is spoken with a freshness, a puzzlement, which makes it seem as though there had never been any scripts or rehearsals, as though she really has just heard this idea for the first time.

Ferrari can be quite eloquent: shrewdly looking at Ilsa "I observe that you are in one respect a very fortunate man, M'sieur. I am moved to make one more suggestion, why, I do not know, because it cannot possibly profit me, but, have you heard about Signor Ugarte and the letters of transit?" . . .

That evening we're at Rick's again.

Yvonne comes in with a German officer who gets in a fight with a Frenchman; Rick shows strength and decisiveness in breaking them up.

The Bulgarian girl Annina approaches Rick and starts talking about Captain Renault. Rick, in a very natural and unselfconscious gesture, rubs his forehead with his index and middle finger -- as though what Annina is about to say could easily give him a headache. She asks Rick's opinion of Captain Renault's trustworthiness, "Will he keep his word?". Rick responds honestly, "He always has." But as to the larger question of whether this (having sex with Captain Renault in exchange for exit visas) is what she should do, Rick is more brutal:

<Rick:> "You want my advice?"

<Annina:> "Oh, yes, please."

<Rick:> "Go back to Bulgaria."

<Annina:> "Oh, but if you knew what it means to us to leave Europe, to get to America! Oh, but if Jan should find out! He is such a boy. In many ways I am so much older than he is."

<Rick:> "Yes, well, everybody in Casablanca has problems. Yours may work out. You'll excuse me."

The artificiality of the girl's acting is in marked contrast to that of Ingrid Bergman, but she can be forgiven much; there's a sweetness, an innocence about her; the actress, Joy Page, was only 17 at the time.

Despite his harsh words, Rick turns around and lets Annina's husband win at roulette, saving her from her fate. I like his stiffness, discomfort, as he is hugged by Annina -- not something he's used to, these public displays of affection.

There's something authentically touching about this strong, capable man, professing indifference, giving several thousand francs to this young couple. It prompts Captain Renault to accuse him of being a "rank sentimentalist".

At this point Laszlo has a private conversation with Rick, trying to convince him to sell the letters of transit:

<Laszlo:> "You must know it's very important I get out of Casablanca." simply "It's my privilege to be one of the leaders of a great movement. You know what I have been doing. You know what it means to the work, to the lives of thousands of people that I be free to reach America and continue my work."

<Rick:> "I'm not interested in politics. The problems of the world are not in my department. I'm a saloon keeper."

Rick and Laszlo hear the sound of male voices singing downstairs. From the top of the stairs outside the office Rick sees a group of German officers around the piano singing the"Wacht am Rhein." Rick's expression is dead-pan. Below, at the bar, Renault watches with raised eyebrow. Laszlo has come out of the office. His lips are very tight as he listens to the song. He starts down the steps, passes the table, where Ilsa sits, and goes straight to the orchestra. Yvonne, sitting at a table with her German officer, stares down into her drink. Laszlo speaks to the orchestra: 'Play the Marseillaise! Play it!' [Koch, p. 175]

No wasted time here: -Bang!- The bandleader looks at Rick. -Bang!- Rick nods. -Bang!- The band starts.

The whole scene is very moving and effective. Some of you may find it rather chauvanistic, melodramatic. Please remember that the great, proud French nation was now under German dominion. Many of the people on that cafe set at the Warner Bros.' studio that day had known German dominion first hand.

"Of the seventy-five actors and actresses who had bit parts and larger roles in Casablanca, almost all were immigrants of one kind or another. . . .

"'If you think of Casablanca and think of all those small roles being played by Hollywood actors faking accents, the picture wouldn't have had anything like the color and tone it had,' says Pauline Kael.

"Dan Seymour [guard to the door of Rick's gambling room] remembers looking up during the singing of the Marseillaise and discovering that half of his fellow actors were crying: 'I suddenly realized that they were all real refugees,' says Seymour." [Harmetz, pp. 212-3]

The actress who plays Yvonne was French (Madeleine LeBeau). If Victor seems rather wooden at other times, only half a man, here we see him in his strength. Perhaps the other bar patrons would eventually have had the courage to defy the Nazis and express their real feelings -- but I doubt it.

Rick and Ilsa do not sing. Ilsa looks at Victor with pride. She believes in the value of freedom, in a world of "knowledge and thoughts and ideals", as much or more than these other people. It would be the easiest thing in the world for her to let her voice join that of her husband and his comrades, to join the crowd -- but that's not her style. . . .

Strasser punishes the cafe's patrons by making Captain Renault find a reason to shut it down. His choice is blatantly hypocritical:

<Rick:> "How can you close me up? On what grounds?"

<Renault:> "I am shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on in here!

<Croupier:> "Your winnings, sir."

<Renault:> "Oh. Thank you very much." turns to the crowd again "Everybody out at once!"

Strasser, finding Ilsa alone, uses the opportunity to bully her. Ilsa demonstrates considerable strength and bravery in standing up to him. His parting shot, "My dear Mademosielle, perhaps you have already observed that in Casablanca, human life is cheap. Good night, Mademoiselle." is delivered in a sinister, threatening tone which words on a printed page only begin to hint at. <Include entire scene, Marseillaise through Strasser and Ilsa, in multimedia version.>

When Ilsa and Laszlo have returned to their hotel room, Victor tells her that Rick has the letters but won't sell them.

<Ilsa:> "Did he give any reason?"

<Laszlo:> "He suggested I ask you."

<Ilsa:> "Ask me?"

<Laszlo:> "Yes. He said, 'Ask your wife.' I don't know why he said that."

Laszlo is surprised that Ricks's relationship with Ilsa is such that it could affect this decision and also that Rick knows of their marriage. This is supposed to be a secret; apparently Ilsa has told him.

Ilsa realizes that she must go see Rick. She refuses to tell Victor anything about him. It seems her relationship with Victor is lacking in physical passion and real intimacy. Even at this critcal point with Ilsa likely to go see Rick, he can manage nothing more than a peck on the cheek. Victor leaves to go to the Resistance meeting; Ilsa goes to get the letters of transit.

Rick walks up the stairs to his apartment. It is dark. When the door opens, light from the hall reveals a figure in the room. Rick lights a small lamp. There is Ilsa facing him, her face white but determined. Rick pauses for a moment in astonishment.[Koch, p. 186]

<Rick:> "Your unexpected visit isn't connected by any chance with the letters of transit? It seems as long as I have those letters I'll never be lonely."

<Ilsa:> looks at him directly "You can ask any price you want, but you must give me those letters."

<Rick:> "I went through all that with your husband. It's no deal."

<Ilsa:> "I know how you feel about me, but I'm asking you to put your feelings aside for something more important."

<Rick:> "Do I have to hear again what a great man your husband is? What an important cause he's fighting for?"

<Ilsa:> "It was your cause, too. In your own way, you were fighting for the same thing."

<Rick:> "I'm not fighting for anything anymore, except myself. I'm the only cause I'm interested in."

A pause. Ilsa deliberately takes a new approach.

<Ilsa:> "Richard, Richard, we loved each other once. If those days meant anything at all to you . . ."

<Rick:> harshly "I wouldn't bring up Paris if I were you. It's poor salesmanship."

<Ilsa:> "Please. Please listen to me. If you knew what really happened, if you only knew the truth . . ."

<Rick:> cuts in "I wouldn't believe you, no matter what you told me. You'd say anything now, to get what you want."

<Ilsa:> her temper flaring, scornful "You want to feel sorry for yourself, don't you? With so much at stake, all you can think of is your own feeling. One woman has hurt you, and you take your revenge on the rest of the world. You're a, you're a coward, and a weakling." breaks "No. Oh, Richard, I'm sorry. I'm sorry, but, but you, you are our last hope. If you don't help us, Victor Laszlo will die in Casablanca."

[Not "Victor". Not "my husband". He means less to her in his capacity as a husband than he does as "Victor Laszlo", the institution, the political force.]

<Rick:> "What of it? I'm going to die in Casablanca. It's a good spot for it." He turns away to light a cigarette. Turning back to Ilsa "Now, if you . . ."

He stops short as he sees Ilsa. She is holding a small revolver in her hand.

<Ilsa:> "All right. I tried to reason with you. I tried everything. Now I want those letters." For a moment a look of admiration comes into Rick's eyes. "Get them for me."

[This is the Rick who responded to Major Strasser's threats with "Are my eyes really brown?" -- a man whose reaction to this gun pointed at him can be interest and admiration.]

<Rick:> "I don't have to. I got them right here."

<Ilsa:> "Put them on the table."

<Rick> shaking his head "No."

<Ilsa:> "For the last time, put them on the table."

<Rick:> "If Laszlo and the cause mean so much to you, you won't stop at anything. All right, I'll make it easier for you. Go ahead and shoot. You'll be doing me a favor."

[Until this last statement, it seems that Rick is saying "I don't believe you. I know you. I don't believe you're so obsessed that you can kill me." But this "You'll be doing me a favor." is startling; we've seen some self-pity when he's drunk but no suicidal tendencies . . . Later Rick will say that they had "lost" Paris but through their experience in Casablanca regained it. But Rick had never really entirely lost Paris. Though Ilsa's actions were difficult to understand, in her parting note she insisted she still loved him. Really losing Paris would be to mean so little to her that she could shoot him for some letters of transit. Could he have been so wrong, so deluded? There's a certain bravado here, but there's also a truth, a feeling that life without love is intolerable. All of this is beautifully under-played. Bogart's voice is matter-of-fact; his face is expressionless.]

Rick walks toward Ilsa. As he reaches her, her hand drops down.

<Ilsa:> almost hysterical "Richard, I tried to stay away. I thought I would never see you again, that you were out of my life." [There is no actress in the world, I repeat, there is no actress in the world who could be so authentically, beautifully, overcome with emotion as Ingrid Bergman is at this point.] walking to the window "The day you left Paris, if you knew what I went through! If you knew how much I loved you, how much I still love you!"

Rick has taken Ilsa in his arms. He presses her tight to him and kisses her passionately. She is lost in his embrace.

In coming here to get the letters, she realized there was a danger of her succumbing to Rick's love, a love which offers exactly what her marriage lacks: physical passion, real intimacy -- with a man who is, in his own way, every bit as admirable as Victor Laszlo.

What makes Rick Blaine and Ilsa Lund so compelling? On the surface there's the interest of Ilsa's great passion rubbing up against Rick's rough matter-of-factness (a combination we see in more exaggerated form in The African Queen), but even more compelling is the deathly seriousness underneath -- two great actors again and again finding in themselves true feelings which realize the high drama with which the writers have challenged them.

The story resumes "sometime later" that same evening. Though they're still fully dressed, the implication is that there has been some physical intimacy. The production code of that time would not have permitted -- in view of the fact that Ilsa was married -- anything more overt.

Ilsa fills Rick in on what was really happening in her life when they were in Paris. And then

<Rick:> ". . . But it's still a story without an ending." looks at her directly "What about now?"

<Ilsa:> "Now? I don't know." simply "I know that I'll never have the strength to leave you again."

<Rick:> "And Laszlo?"

<Ilsa:> "Oh, you'll help him now, Richard, won't you? You'll see that he gets out? Then he'll have his work, all that he's been living for."

<Rick:> "All except one. He won't have you."

<Ilsa:> "I can't fight it anymore. I ran away from you once. I can't do it again. Oh, I don't know what's right any longer. You'll have to think for both of us, for all of us."

<Rick:> "All right, I will. Here's looking at you, kid."

<Ilsa:> "I wish I didn't love you so much."

It's not easy to play a woman who has drawn a gun on a man and moments later doesn't have the strength to ever leave him again. . . . Her expressions vary rapidly from smiling to serious; she shakes her head confusedly. <Please include entire scene between Rick and Ilsa in multimedia version.>

The fascinating thing about this situation is the idea that she may, even now, be doing this just to get the letters for Victor. If she really loves Rick, why did it take the letters to bring her to him? Is she simply sacrificing herself for Victor, resigned to staying unhappily with Rick in Casablanca, perhaps trying to get out herself later? Or does she somehow intend to use the second letter herself so that both she and Victor can escape? (In regard to this latter possibility, I would point out that Ilsa does not continue to seek the letters and never actually has them in her possession, and that her confusion and regret in the final scene seem perfectly genuine.)

Laszlo comes to Rick's after the meeting:

<Laszlo:> "I know a good deal more about you than you suspect. I know, for instance, that you are in love with a woman." smiles just a little "It is perhaps a strange circumstance that we both should be in love with the same woman. The first evening I came here in this cafe, I knew that there was something between you and Ilsa. Since no one is to blame, I, I demand no explanation. I ask only one thing. You won't give me the letters of transit. All right. But I want my wife to be safe. I ask you as a favor to use the letters to take her away from Casablanca."

Rick looks at Laszlo incredulously.

<Rick:> "You love her that much?"

<Laszlo:> "Apparently you think of me only as the leader of a cause. Well, I am also a human being." looks away for a moment, then quietly "Yes, I love her that much."

The French police (no doubt at Strasser's instigation) arrest Victor on a petty charge. Rick convinces Renault that he plans to use the letters of transit to go to Lisbon with Ilsa, and that he wants to help Renault frame Laszlo on the bigger charge of possessing the letters of transit. Renault will release Laszlo; Rick will lure him to his cafe where Louis can arrest him.

Victor is freed and comes, with Ilsa, to Rick's at the appointed hour: Victor thinking that he will be buying the letters for Ilsa and himself to use; Renault thinking that Rick and Ilsa will be using them; and Ilsa thinking that Victor, alone, will be using them. Renault, lying in wait, jumps out to arrest Laszlo after Rick has given him the letters.

<Renault:> "Victor Laszlo, you are under arrest on a charge of accessory to the murder of the couriers from whom these letters were stolen." Ilsa and Laszlo are both caught completely off guard. They turn toward Rick. Horror is in Ilsa's eyes. Renault takes the letters.

<Renault:> "Oh, you are surprised about my friend, Ricky? The explanation is quite simple. Love, it seems, has triumphed over virtue. Thank . . ." Obviously, the situation delights Renault. He is smiling as he turns toward Rick. Suddenly the smile fades. In Rick's hand is a gun which he is leveling at Renault.

<Rick:> "Not so fast, Louis. Nobody's going to be arrested. Not for a while yet."

<Renault:> "Have you taken leave of your senses?"

<Rick:> "I have. Sit down over there."

[There's a seriousness to Rick's voice and expression, a hint of the desperation necessary for a sane, feeling man to take another person's life.]

Rick has Renault call the airport to tell them that there will be passengers using the letters of transit that night and there's to be no trouble. But Renault only pretends to be calling the airport, instead he dials Major Strasser, alerting him to the fact that something irregular is going on.

The scene at the airport is a masterpiece of pacing and suspense. The setting is quickly established by the orderly calling the radio tower with data on visibility, ceiling, etc.

<Rick:> "I'm staying here with him 'til the plane gets safely away."

<Ilsa:> as Rick's intention fully dawns on her "No, Richard, no. What has happened to you? Last night we said . . ."

<Rick:> "Last night we said a great many things. You said I was to do the thinking for both of us. Well, I've done a lot since then and it all adds up to one thing. You're getting on that plane with Victor where you belong."

<Ilsa:> protesting "But Richard, no, I, I . . ."

<Rick:> "Now you've got to listen to me. Do you have any idea what you'd have to look forward to if you stayed here? Nine chances out of ten we'd both wind up in a concentration camp. Isn't that true, Louis?"

<Renault:> as he countersigns the papers "I am afraid that Major Strasser would insist."

<Ilsa:> turns to Rick "You're saying this only to make me go."

<Rick:> "I'm saying it because it's true. Inside of us we both know you belong with Victor. You're part of his work, the thing that keeps him going. If that plane leaves the ground and you're not with him, you'll regret it."

<Ilsa:> "No."

<Rick:> "Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon, and for the rest of your life."

<Ilsa:> "But what about us?"

<Rick:> "We'll always have Paris. We didn't have it, we'd lost it, until you came to Casablanca. We got it back last night."

<Ilsa:> "And I said I would never leave you!"

<Rick:> "And you never will. But I've got a job to do, too. Where I'm going you can't follow. What I've got to do, you can't be any part of. Ilsa, I'm no good at being noble, but it doesn't take much to see that the problems of three little people don't amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. Someday you'll understand that. Not now. Here's looking at you, kid."

[Louis later calls this a "fairy tale" -- and contends that Ilsa knew he was lying.

Rick's last argument, "You can't go where I'm going", has problems. It seems he has decided to go join the Resistance but, at this point, is more likely to be going to jail. Before Victor was arrested, Rick could have quietly given him the letters and avoided this whole situation. Even after, he could have waited until Victor was released. (As he himself has noted to Louis, "All you can do is fine him a few thousand francs and give him thirty days.") Thus, leaving himself free to contribute to the Resistance in a way which would not have precluded Ilsa's being with him.

The second argument, "We'll always have Paris" (and, therefore, won't need to actually be with each other) shows Rick as the ultimate romantic: it's not the physical presence that matters, but the knowledge of love, its certainty. There's something to this, especially as it pertains to the highest and most noble natures,-- but one wonders how well it will wear over time. Perhaps Ilsa will regret her abandonment of Rick more than she would have ever regretted leaving Victor. . . . "Paris" is a poor substitute for actually being together, and they both know it.

The first argument, "Victor needs you", is less easily dismissed. It seems that Ilsa is important to Victor -- even if it's hard to understand just how. And Victor's work is extremely important. If Ilsa adds even moderately to its success, her action can, in the calculus of war, be justified.]

Laszlo returns and Rick tries to allay the suspicions he assumes Victor has about his relationship with Ilsa.

<Rick:> his voice more harsh, almost brutal "She tried everything to get them, and nothing worked. She did her best to convince me that she was still in love with me, but that was all over long ago. For your sake, she pretended it wasn't, and I let her pretend."

[There's a complexity here, a depth to this situation, in that we can't completely discount the possibility that Ilsa was pretending.]

Major Strasser arrives as the plane is departing. He picks up the phone to call the Radio Tower.

Strasser, his one hand holding the receiver, pulls out a pistol with the other hand and shoots quickly at Rick. The bullet misses, but Rick's shot has hit Strasser, who crumples to the ground.

A police car speeds up to the hangar. Four gendarmes jump out. In the distance, the plane is turning onto the runway. The gendarmes run to Renault. Renault turns to them.[Koch, p. 226]

<Gendarme:> "Mon Capitaine!"

<Renault:> "Major Strasser's been shot." pauses as he looks at Rick, then to the gendarmes "Round up the ususal suspects."

[Louis' words strike us like a thunderbolt. Wasn't it less than ten minutes ago that he insidiously alerted Major Strasser? Didn't he, just moments before, suggest that he would have to arrest Rick? How can he get away with it? . . . Then it dawns on us: there are no other witnesses. . . . But why? Isn't he the ultimate pragmatist? What can he possibly gain from this? . . . It seems that he's undergone a conversion.]

<Renault:> "Well, Rick, you're not only a sentimentalist, but you've become a patriot."

<Rick:> "Maybe, but it seemed like a good time to start."

<Renault:> "I think perhaps you're right."

Of course he was highly susceptible, having never really been pro-Vichy to begin with. It seems these dramatic events -- especially Rick's example -- have compelled him to take a stand. They decide to go together to join the Free French garrison at Brazzaville. "Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship."

Casablanca is about the decision of one particular American to forgo a particular personal relationship for the good of humanity, to join the fight against Fascism. We have seen throughout, Rick's attempts to deny his past, to convince himself that "the problems of the world are not in my department" -- though we have also been prepared (by the Annina/roulette subplot) for how Rick can preach cynicism and practice something quite different.

And Casablanca is, by extension, also about the decision of Rick's native country, the United States, to join the fight against Fascism. (At the time Everybody Comes to Rick's was written, the U.S. was not yet in the war; by the time the filming of Casablanca was completed, official involvement was still less than eight months old.) And Rick's new-found friendship with Louis has its parallel in the United States' alliance with France (and with Europe as a whole).

These parallels are interesting and add a certain resonance to the movie, but its heart is in the characters as individuals, their private lives and the tension between those lives and public obligations.

We live in a gray, uncertain time. We question whether life is really important. Meaningful relationships seem impossible.

Casablanca is a letter from the past. It says that life is extremely important. And that not only is love possible, it can reach to the very deepest parts of our being. And how we live (in freedom and under the rule of just law) is so important that noble people will willingly sacrifice even such deep love for it. . . .

In the darkest hours of World War II, on a Warner Bros.' studio backlot, a hundred people got together to act out and record what promised to be a fairly standard entertainment of love and intrigue. Somehow, what resulted was much more: a rich, supremely life-affirming fable of duty and love.

CASABLANCA

Oh Rick, if only things were so simple. . . .

If only there were Nazis shooting children,

bullies like Major Strasser waiting to take over,

women like Ilsa --

so beautiful and passionate

that just the memory of their love, just the shadow,

is enough.

We would sing the Marseillaise

and in the air itself,

just breathing in that hot, dry air,

would find all the meaning we need.

But we live in an everyday world,

with everyday human beings.

And we must start again each morning,

with scraps of faith and feeling,

to make the world's meaning in the foundry of our heart.

References

Harmetz, Aljean. Round Up the Usual Suspects: the Making of Casablanca -- Bogart, Bergman, and World War II. New York: Hyperion, 1992. ISBN: 1-56282-941-6.

Koch, Howard. Casablanca: Script and Legend. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 1992. ISBN: 0-87951-319-5.

Links to other Casablanca pages:

Do you know of other art --especially contemporary art available through the Web-- which expresses genuine feeling? Please email me: Lucius@mail.serve.com

Copyright © Lucius Furius 1997; last updated, June, 2002 (added link)

Link back to Genius Ignored --Table of Contents

Link back to main page (Humanist Art Homepage)